THE INNOVATION CENTER

ST. CROIX, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS

PROJECT STATUS | BUILT

PROJECT BACKGROUND

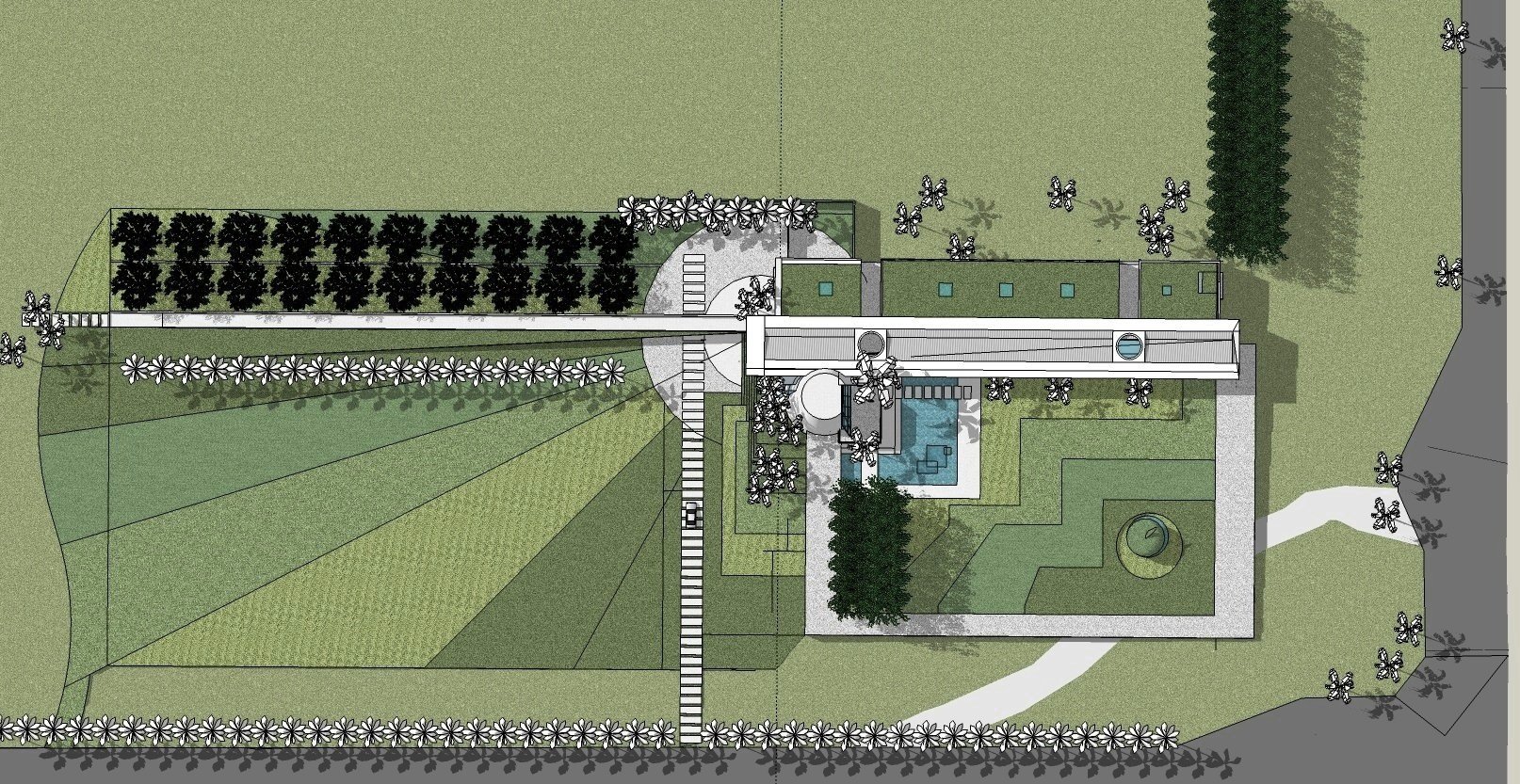

The Research Technology Park (RTPark) is a 10-acre e-commerce and knowledge hub within the University of the Virgin Islands campus on St. Croix. Launched in 2002 as a government-led public–private initiative, its goal was to drive long-term economic growth through technology-based businesses. VA supported planning and design for the Innovation Center, originally conceived in the traditional campus style but later reimagined as a contemporary, LEED-certified building that embodied innovation in both presence and design.

An agreement was made to develop the Innovation Center as an iconic 20,000 SF LEED-certified “green” building, serving as both the headquarters and marketing showcase for Phase One of RTPark. VA assisted in assembling the consultant team, including Architectural Alliance with Scott Andrew Natvig (S.A.N.D.) as Architect of Record, Williamsburg Environmental Group as hydrology engineers, and other key specialists.

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE

For centuries, sugarcane shaped the economy and culture of St. Croix, leaving a strong imprint on the island’s historic fabric. Today, e-commerce is envisioned as the new industry. The Innovation Building design echoes this continuity—stone walls, garden plots, grids, and sheltering roofs recall the plantation landscape, yet are reinterpreted in a modern, forward-looking expression.

THE MACHINE IN THE GARDEN

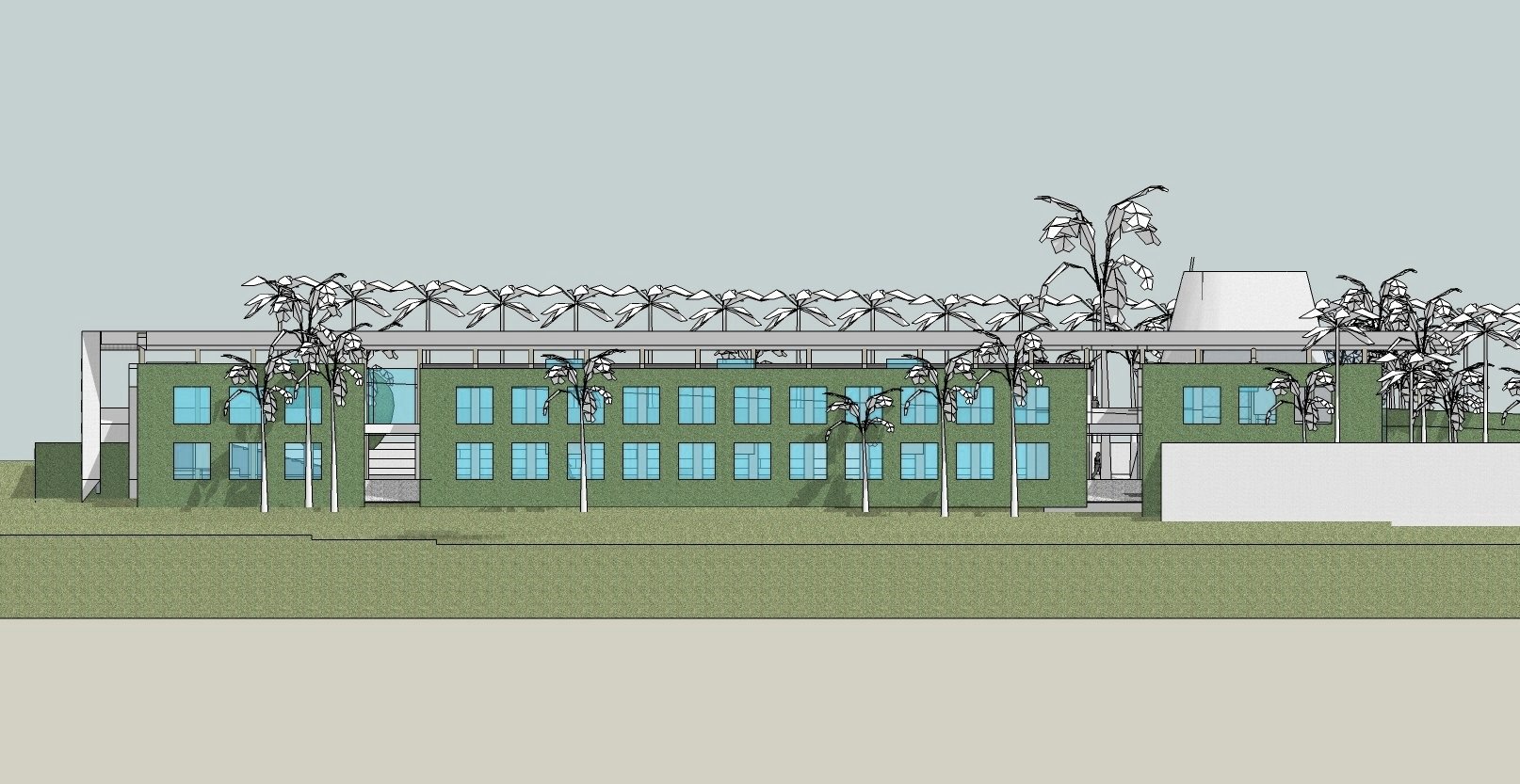

We proposed a long, narrow building stretched across the site—almost like a dam—to symbolically “hold back” stormwater from the university campus and protect the neighborhood downslope. In its presence, the building created a deliberate contrast with the landscape, echoing the “Machine in the Garden” modernist precedents where corporate architecture was set against a pastoral backdrop.

Precedents: Glenn Murcutt: Bowali Visitor Information Center; Peter Walker’s South Coast Plaza & IBM Japan Makuhari; O. Niemeyer+ Roberto Burle Marx, Itamarati.

THE GARDEN AS MACHINE

Unlike the modernist prototype, the landscape was not meant as a backdrop to architecture but as its equal. Here, the Garden itself became the Machine—a functional system of experimental terraces designed to test soil-making through waste reuse and bioretention. Its invisible biological processes underground echoed the building’s own role, aligning form and infrastructure into a single, working landscape.

Precedents : Michel & Claire Corajoud, Parc du Sausset; Clement/Berger & Provost/Viguier, Parc Andre Citroen.

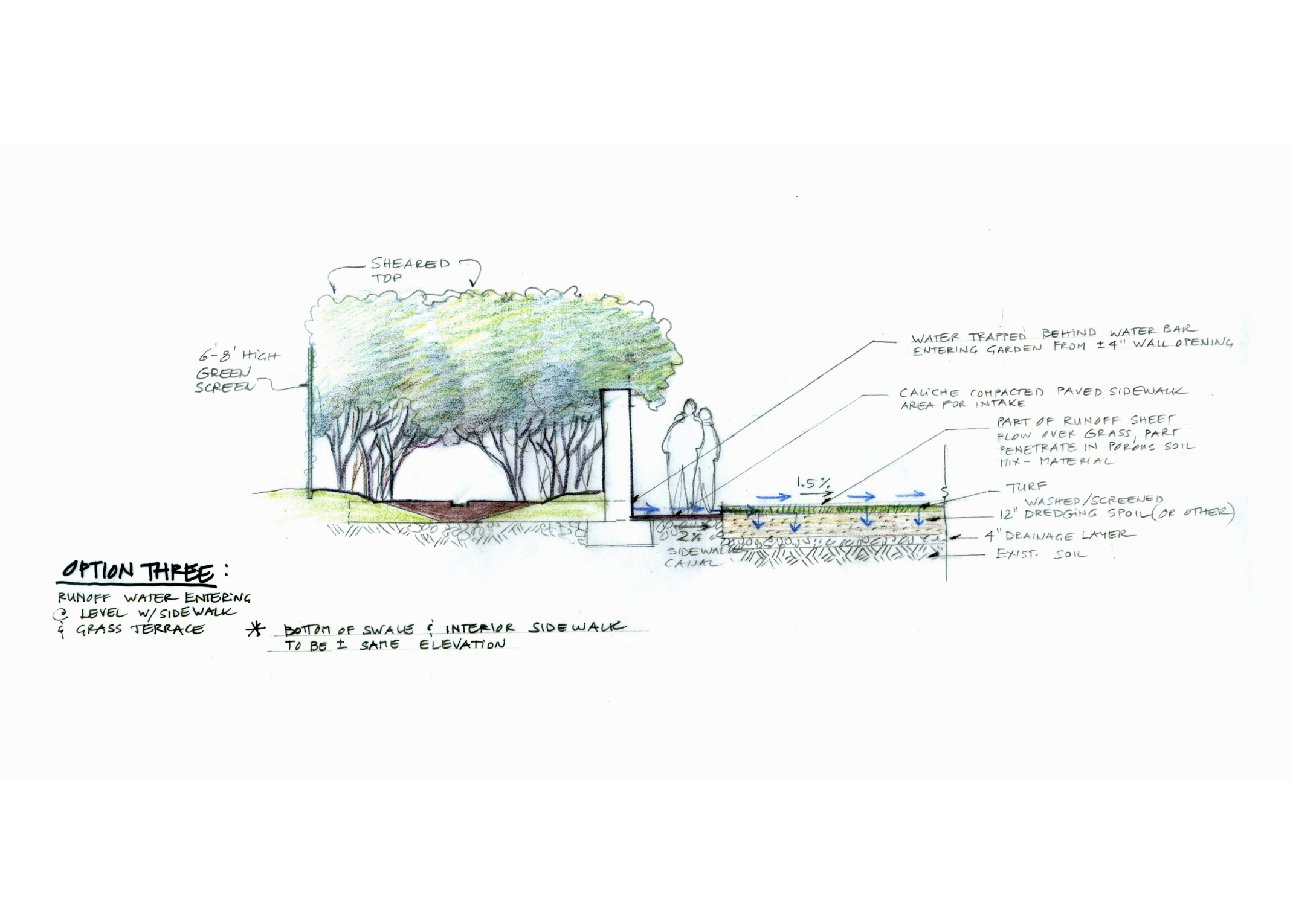

In the early design schemes, stormwater was first collected in a canal along the campus edge, which also served as an elevated walkway in dry seasons. After storms, water would filter by gravity through the experimental plots, with excess flow diverted to a swale near the parking lots. The cleaned runoff was then stored in a cistern and reused to supply a courtyard water garden, helping passively cool the building.

REMADE LANDSCAPES

Phase One envisioned the site as a working laboratory where waste materials were reused to create permeable soil mixes for bioretention. These experimental garden plots would be monitored over time, adapting plantings to local hydrology and reducing reliance on imported resources.

Dredged sediment, bagasse, quarry waste, composted wood, cattle manure, and recycled glass were all repurposed for soil mixes, paving, and structural elements. Even caliche-carbonate, a difficult local substrate, was reused for berms, levees, and aggregates. Early plantings introduced tall palms for structure, while native trees were grown in pots until ready for transplanting.

The test plots evaluated erosion control, infiltration, and plant resilience under alternating drought and flood. As trees matured, they were relocated to campus areas or site edges, making room for new planting cycles.The result was an adaptive, phased landscape strategy: recycling waste, shaping hydrology, and evolving the garden through continual renewal.

Michel Desvigne, le jardins elementaries; Clement/Berger, Parc Citroen; Noguchi’s California Scenario

FROM TEST LOTS TO GRASS FIELD

The client was reluctant to pursue an evolving experimental landscape, leading to a simpler parterre of two contrasting grasses. Managed through natural growth and selective mowing, it revealed shifting patterns and gradients of green across storms and seasons.

One of the two grass species could be left to grow naturally, or alternately shaped by mowing to reveal patterns and aid filtration. After storms, the sloping field displayed shifting gradients of green—from dry upper slopes to wetter areas by the swale. Soil production from waste was relocated to holding plots at the back of the site.

Greater emphasis was placed on the inner courtyard, where a stepped garden filtered runoff from the northeast corner. Its edge formed a hedge-swale of native plants, resilient to both flood and drought, shaped outward by a greenscreen for a formal frame without clipping. Stormwater was guided from the hedge-swale into the terraces through weirs.

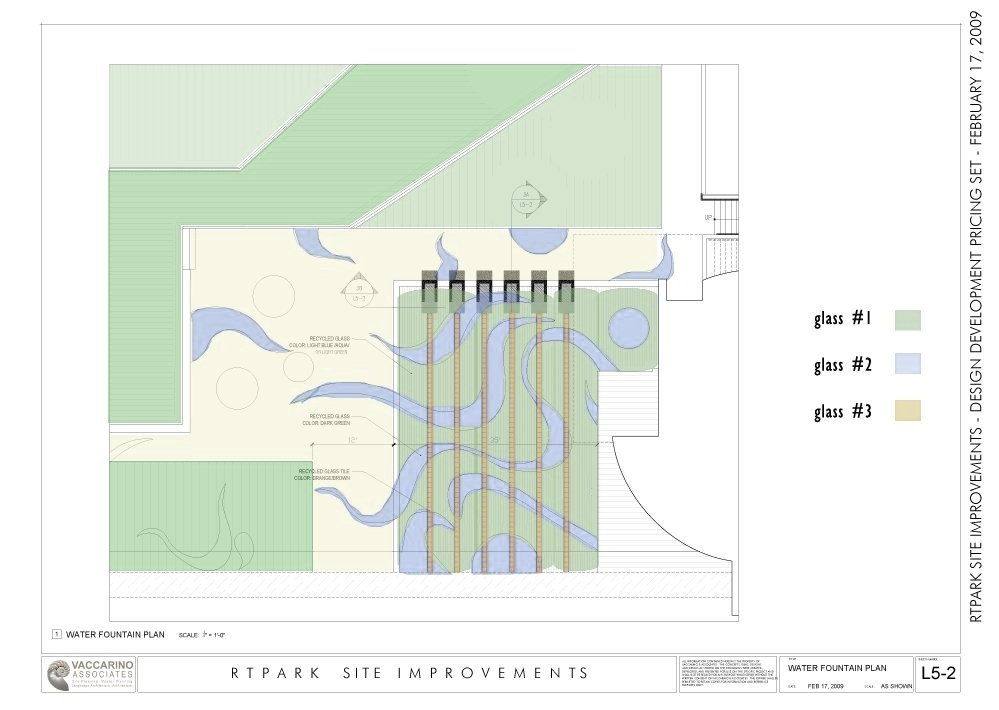

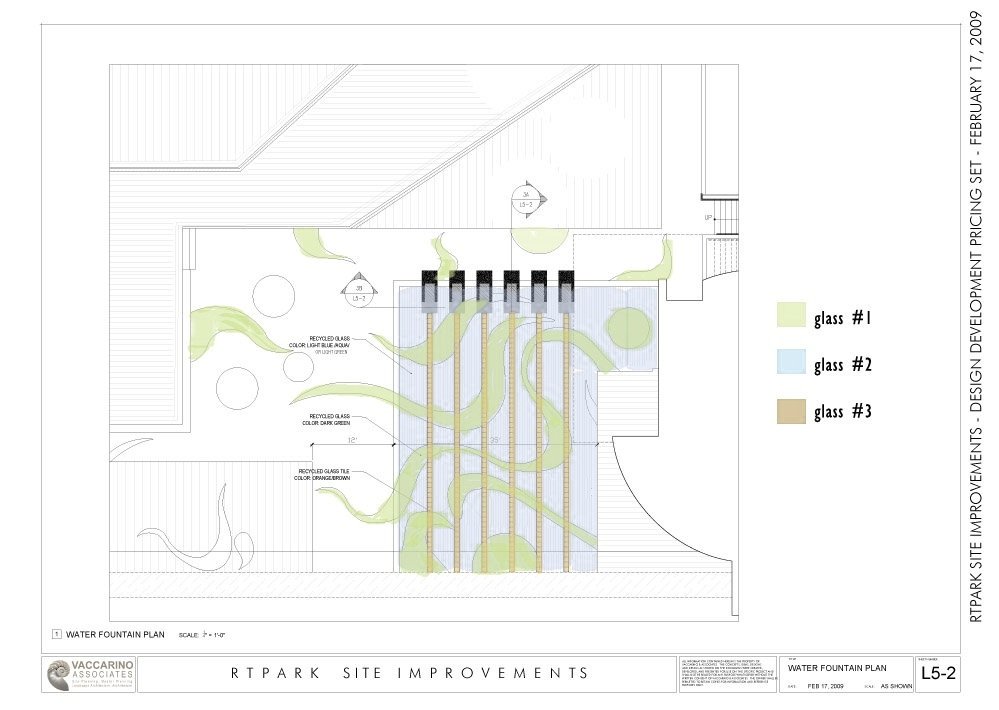

A parallel canal then gathered the filtered water, cooling the building as breezes carried its humidity. Canal flow and rainwater from the roof fed cisterns beneath a water parterre paved in blue-green-gold recycled glass—a metaphor for water in dry spells. The parterre revealed water only in the wet season, hiding it safely within cisterns the rest of the year.

A convex canopy was added on the roof harvest rainwater into cisterns beneath the building, while a greenscreen shaded the west façade. At the university’s request, a nod to Danish plantation windmills was reinterpreted through a contemporary turbine in the courtyard, framed by palms and a grid geometry. Together, building and garden acted as a working machine—a cultural landscape where history and innovation converged through an environmentally conscious design.

AFTERWARDS

This $13 million project broke ground in September 2011 but was heavily value-engineered, stripping away most of its original design intent. The grass parterre was replaced with a plain lawn and rows of foxtail palms, while the courtyard garden and water-glass parterre were never built. Without construction administration from our part, implementation suffered: staked trees bent, palms looked skeletal, and bromeliads were scattered as decoration. Even the rooftop canopy—once the project’s symbol of water harvesting—was eventually removed.