FLAMENCO BEACH

SITE ASSESSMENT AND PROPOSAL FOR RECOVERY

PROJECT STATUS | IN PROGRESS

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The Flamenco Beach Recovery Project in Culebra, Puerto Rico, focuses on strengthening the natural systems of its coastal forest, dunes, and hydrology. The project was initiated after the devastation inflicted by Hurricanes Irma and Maria to provide with enhanced protection from future coastal climate events and natural hazards, engaging its residents as active participants in the recovery and management operations.

The project is part of a larger initiative, Rebuilding Playa Flamenco, which for years has worked to rebuild the beach facilities and its natural assets as a strategy for establishing community resilience in Culebra. In this project, we do not want to use the word “restoration” to a fixed period of history. By “recovery” or “rehabilitation” we mean setting in motion the process for achieving the highest possible level of function, independence, and biodiversity in the site after the trauma suffered from Hurricanes Irma and María.

Vaccarino Associates led the planning and design efforts for Paralanaturaleza.org, which is the organization coordinating the reforestation and recovery of the dunes. We have made clear from the beginning that if no recovery actions are taken soon, Flamenco Beach is at imminent risk of disappearing when another large climate event impacts the area.

LOCATION

Flamenco Beach is located on the island-municipality of Culebra, 17 miles from the northeast coast of Puerto Rico. The 11- square-mile island holds a population of 1,600. The beach is bordered on the east and west by the U.S. Culebra National Fish and Wildlife Refuge. An important nesting site for endangered sea turtle species, the beach is protected by a fringing coral reef system where A. palmata and A. cervicornis are found.

AN INNOVATIVE APPROACH

The Flamenco Beach Recovery Project is an interdisciplinary, replicable, and collaborative effort. It integrates the community in the process of rehabilitation and preservation of the coastal forest, water and dune systems, allowing them to implement and learn the value of conservation practices including water reuse and green infrastructure. The project proposes a five-pronged approach

- Coastal reforestation using endemic and native species missing from the surviving existing trees.

- Rehabilitation of forest, dunes and freshwater pond habitats at an ecological level in a highly accessible and visible area, while providing recreation and education for the community and visitors alike.

- Creation of entrepreneurship opportunities in Culebra that support conservation of habitats while building resilience.

- Active participation of the community in the recovery, maintenance and conservation of the coastal forest, water and dune systems, increasing community ownership and long-term monitoring and commitment.

- The adoption of a mitigation action plan, parallel to the recovery plan, which addresses both preparation and response for future climatic events, through adaptive planning and the development of guidelines for the benefit of visitors and residents.

CONTEXT

The world-renowned Playa Flamenco, or Flamenco Beach, is known for its shallow turquoise waters, pristine white sands, swimming areas, and diving sites. In March 2014, Flamenco was ranked 3rd best beach in the world with a Trip Advisor Travelers’ Choice Award. Prior to the impacts of hurricanes Irma and María, the beach was stretching for a mile on a horseshoe-shaped bay and received well over 700,000 visitors a year. The beach and its facilities are the principal economic drivers of income for both the Culebra Municipality and its residents, generating $2 to $3 million annually.

The Autonomous Municipality of Culebra owns the beach land and shares the responsibility for the administration of Flamenco Beach with the Authority for the Conservation and Economic Development of Culebra (ACDEC). Hurricanes Irma and María battered the small island of Culebra with widespread devastation and massive destruction. Flamenco Beach was left in ruins, its dunes ravaged, trees toppled or destroyed, shrubs, soil and organic matter blown away, and debris strewn everywhere, on land and water. The economic crisis in Puerto Rico, magnified by the hurricane events of 2017, has limited the municipality’s and ACDEC’s ability to restore the beach and rebuild its facilities.

KEY PROJECT PARTNERS

The Municipality of Culebra and ACDEC established a collaborative agreement with The Foundation for a Better Puerto Rico, a private NGO, as follows: while the Foundation conducts fundraising and seeks grants for the buildings and capital improvements on Flamenco Beach, Para la Naturaleza (PLN, another NGO) assumes the responsibility for the coastal forest, dune restoration, water retention, and recycling infrastructure needs. Proyecto Siembra, an AmeriCorps initiative conducted by Mujeres de Islas, will support PLN in the coastal forest and dune restoration activities along the beach, and we expect many other groups will want to participate in the implementation phase of the project.

PLN brings together every person who wants a sustainable future for Puerto Rico. Created in 2013 through the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico, PLN is responsible for the Trust’s operations in five geographical regions that serve Puerto Rico and its islands, protecting more than 35,000 acres. Accredited by the Land Trust Alliance Commission Accreditation, certifying that its operations meet the rigorous standards and practices in conservation, PLN is the first organization in Puerto Rico to be admitted to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

SOCIAL RESILIENCE

Since the signing of the collaborative agreement, over 200 volunteers have participated in beach cleanup days, allowing the campground to reopen. The Foundation performed repairs to the existing buildings to make them operational again, while the new facilities and infrastructure were being redesigned. Workers were hired to manage the beach while ACDEC developed plans for financial self-sufficiency. Through the engagement of residents and volunteers in the needed reconstruction and management practices, both natural and social resilience are enhanced.

Plans for the facilities have been completed and submitted for permitting. The Foundation has raised $1.6 million of the $2.2 million required for the general infrastructure and facilities components. PLN has assigned Vaccarino Associates (VA) to perform an assessment of the existing trees, to develop site planning and design for the recovery of the site, dunes, and water infrastructure, as well as assist with the plant selection for propagation and replanting. A summary of the work in progress is incorporated in this page.

PROJECT SCOPE AND TIMELINE

A more in-depth analysis of the site, with an evaluation of its opportunities and constraints. Would expand the programmatic scope and financial involvement of PLN beyond the original commitment of helping with reforestation alone. (The major points are described below.)

- The expertise of dune restoration scientists is required to recover the dunes and its vegetation. We also need to start growing many shrubs and herbaceous plants native to the Flamenco Beach coastal ecosystem that are absent in the plant propagation facilities of PLN in Puerto Rico.

- A plant nursery with propagation areas and mist room for cuttings is proposed as a critical part of the funding needs. It will allow to grow on-site the coastal plants, dune grasses and ground cover species in the large quantities needed to restore 800 linear meters of eroded coastline. These dune plants do not survive transportation well. However they would thrive if propagated very close to the ocean microclimate from locally collected seeds and cuttings. The nursery facility will be the place to train staff and volunteers on how to grow, plant and maintain the beach dunes and its coastal forest behind.

- The Site Recovery Project budget now includes also a soil preparation and composting area where amendments and new soil will be produced from recycling leaf litter and organic matter currently discarded. Planting soil, a material that is quite expensive and not available in Culebra, is needed locally to replant all areas.

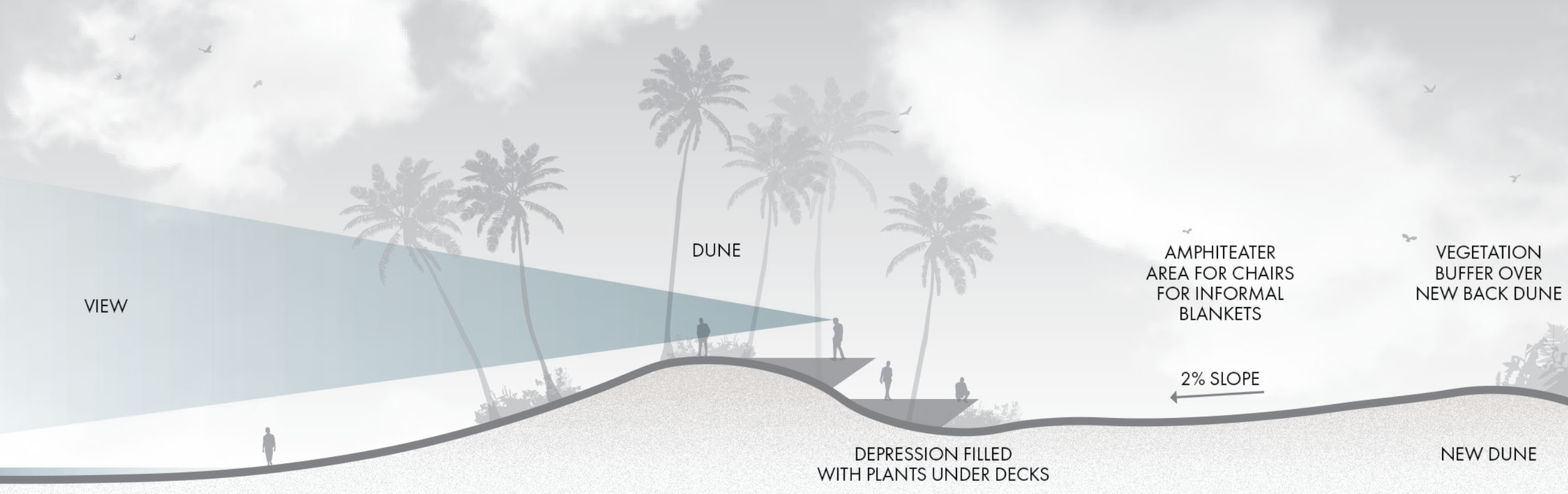

- A system of fencing, dune walkovers and platforms will be needed, as later illustrated in this book, which will help dune regeneration while protecting the dune plants from beachgoer’s abuse.

- Finally, the design of an integrated system of water infrastructure will include hydrology studies, environmental engineering and the input from a wetland ecologist.

The proposed system includes:

1) design of the parking lot and plant nursery as stormwater retention areas

2) reclamation of the freshwater pond, which receives stormwater to be reused for irrigation after filtration

3) construction of vegetated swales and bioretention beds for stormwater and gray water filtration, conveyance and reuse

4) cisterns to capture rainwater from the new building roofs for reuse in bathrooms

5) a self-contained, on-site alternative sewage treatment system, desirable to avoid black water contamination that produces clean water effluent rich in nutrients for irrigation or other non-potable reuse. PLN and the other project Partners are actively seeking the funds necessary to support this comprehensive approach to recover Flamenco Beach’s natural ecosystems and prepare the site for long-term response to potential future climatic impacts

The responsible and efficient use of the campgrounds, vegetation, dunes and water are the foundation of a strong, environmentally sound recovery. There cannot be one without the other. This project will demonstrate that the best solution to a problem often comes from reframing the question of what is really needed. The integration of all site issues and critical rehabilitation priorities with the building and infrastructure design will create solutions that are adaptable to climate change and long term sustainability. We hope that our successful model will be replicated in future projects and other islands.

PLANT COMMUNITIES

We understand that plant community dynamics and vegetation management are intricately interrelated, and a good grasp of the basic process involved in vegetation change is beneficial for the sound interpretation and manipulation of plant communities, especially when addressing climate change. Since natural ecosystems have been, and are being, increasingly modified by human activities, restoring and preserving landscape diversity are major aspects of applied ecology.

Despite the specialty of this field, we wanted to frame our assessment of the existing vegetation at Flamenco with an understanding of the larger regional scale and describe the plant communities that Flamenco Beach and its surroundings might exemplify as a model or reference for our remediation techniques.

Although we used recent U.S. Forest Service Land Cover maps, this classification is still preliminary. Due to the potential presence of mines from previous U.S. Military activities, we cannot inspect by foot the Coastal Forest and Woodland communities to the south of Flamenco Beach’s property boundary. Plant biologists probably have not physically inspected the land to the south of the site in the last 30+ years to determine in different seasons the % of evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs to classify correctly the various plant community types. Therefore, the vegetation maps available are neither reliable nor detailed enough. Furthermore, the impact of Irma and María on the vegetation makes the mapping information available outdated, and the classification even more difficult.

EXISTING TREE SURVEY

The survey we received to perform our study presented tree symbols in the drawings for their location. However, it did not indicate tree names, canopy size, and did not mention health conditions post-hurricane. Many smaller caliper trees and all shrubs and herbaceous plants were omitted as well, yet this information was necessary for us to assess the storm damage on the dune and on the managed forest landscape.

The architectural proposal, already in design development, did not have enough information from this kind of tree survey to protect the important existing vegetation from proposed buildings, parking lots, and roads. As a consequence, the proposed reconstruction plan eliminated a large number of trees to make space for the needed facilities in the program.

EXISTING TREE INVENTORY

Almost 1000 trees were surveyed during our site inspection in October 2018, along with as many shrubs and dune plants as possible, to understand the vitality of the vegetation and its potential recovery. We created an inventory whereby each tree was assigned a progressive number with its common and botanical name, stating whether it was native, non-native, naturalized, or an invasive species.

In the plant identification process, we discovered that only a few coastal tree species were abundant throughout the site, which means Flamenco Beach has very little botanical diversity. We also measured, for each tree, the trunk diameter at breast height, the clear trunk to pass under, the canopy size, and approximate canopy shape to determine its spread and land cover. This allows us to determine appropriate land use and circulation patterns. We then compared our measurements on-site with the drone aerial photography made available to us.

EXISTING TREES TO ELIMINATE

We assessed the general health conditions of the existing trees and determined which should be retained or eliminated if too heavily damaged by the hurricanes. We also included in the elimination list those exotic species that are displacing native coastal species that could potentially be there without such competition.

Many trees in the campground show signs of decline due to a lack of organic matter, soil compaction, and vandalism from campers. Nails and ropes are driven into limbs and trunks, and signs of campfires are visible in the middle of some tree trunks in many areas. Dry but still alive limbs from hurricane damage have been, and continue to be, cut down by people to hold tarps and rain covers.

EXISTING TREES TO PRUNE

Trees that need urgent professional pruning were identified, in order to eliminate dead limbs or dead tips to help correct regeneration. As a sign of survival from the trauma of the hurricane, many of them show heavy proliferation from spurs and suckers at the trunk base, especially if they have been topped or have lost the central leader. Insects attack some others.

Professional pruning to select the healthiest limbs and encourage good form is urgent, as two years have almost passed since the hurricanes: it should have been done right after the storm. The lack of organic matter and topsoil displaced during storms and cleanup efforts have weakened the trees' health further, compromising the possibility of their recovery. PLN has agreed to provide an arborist with the professional qualifications to perform the tree pruning.

Mature trees in the campground are not fertilized nor pruned and do not have organic matter, as leaves are constantly removed to make space for camping. Many are in a state of senescence and therefore more susceptible to storm damage or decay. Tents and cooking equipment placed directly on the trees' root systems over the years have compacted the soil, compromising air and water availability to the roots. Better growing conditions need to be provided when planting new, smaller trees in the campground, protecting them from vandalism and soil compaction by solid fencing.

EXISTING LOW VEGETATION

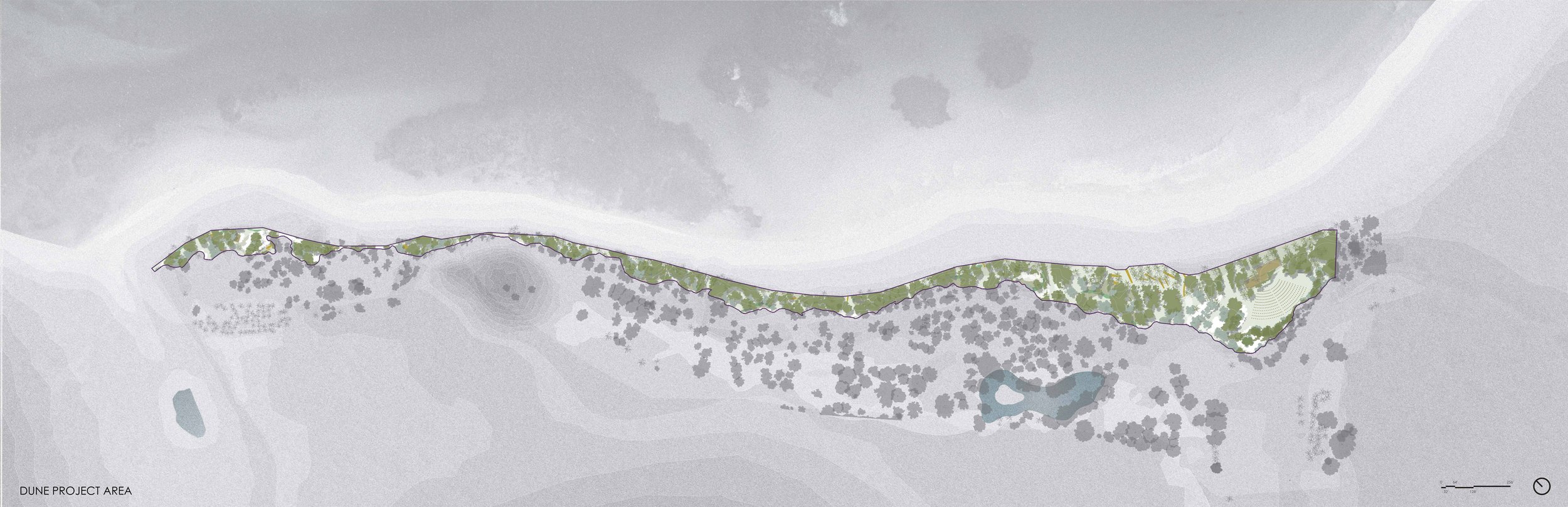

We surveyed the most important areas where the dunes were covered by shrubs, herbaceous plants and grasses of botanical importance. The areas of our work are shown diagrammatically in this plan. In many areas we could not closely inspect a tangle, “in constant movement,” of spiny shrubs, herbaceous plants and vines, growing into each other and colonizing space left from other plants that were blown away by Irma and María.

Before the hurricanes, a continuous fabric of wind-combed, dwarfed shrubs was enveloping the sand dunes like a coat, proliferating towards the water with long extensions of Ipomea pescaprae and Canavallia rosea. That was our image of Playa Flamenco. Grass species were not predominant on the frontal dune zone. The location and expansion of some of the herbaceous perennial and annual plants in the backdune zone mark an interesting contrast between the change and permanence of this landscape.

Many “biological moments” were observed of smaller plants that typically appear and disappear in unexpected places with the seasons and weather—Like Stachytarpheta jamaicensis and Lactuca intybacea. They register water availability or intensity of use and disturbance from beach visitors or maintenance crews. A remarkable difference between October 2018 and February 2019 in many areas was noted. This is suggesting that, indeed, the dunes are the most dynamic, fluid and fragile ecosystem at Flamenco Beach, always changing in response to external forces.

EDITING VS. REPLANTING

Hurricanes Irma and María have displaced trees and plants leaving voids for more competitive exotic plants to thrive and reproduce. Many invasive seedlings where noted in the wet areas around the pond, and especially on the dunes, where, in normal conditions, a thick coastal shrub mass would not allow them to grow.

Some trees that belong to the dry forest zone have now migrated and grow on top of the dunes where they will eventually displace and overshadow the smaller dune plants that are struggling to grow back unless these newcomers are eradicated at the seedling stage. Morinda citrifolia, Leucaena leucoacephala and Terminalia catappa are especially aggressive. We do not want to exert too much control in our editing power in what is a natural process of competition and vegetation change.

However, we want to engage the local community in learning and working together to recognize what should be respected or accepted, and what is too destructive and should be eliminated. What we see right now is a natural reaction of stems and twigs proliferation against the fear of death caused by a traumatic event. Indeed, category five hurricanes like Irma and María seem to be a more destructive and less regenerative force than a fire would be in a natural meadow or savanna landscape.

FACILITY PROGRAM

Prior to the climate events of 2017, the Autonomous Municipality of Culebra, Foundation for Better Puerto Rico, and the School of Architecture of the University of Puerto Rico had already begun the process for redesigning the beach facilities developing a Concept Master Plan for building improvements, trails, campgrounds, and tree planting.

After Irma and María, Architect Andrea Bauzá was hired by the Foundation as a project manager, and BZ Architects were selected to develop further plans and construction documents for the facility buildings, which were almost completed when Vaccarino Associates joined the design team in October 2018. This plan shows the original program.

BUILDING VS. TREES

The first step was to substitute the incomplete tree survey plan previously made available with the new plan showing precise shape, size and location of existing trees developed by Vaccarino Associates. The overlay of the new existing trees plan on the proposed facility program plan allowed us to inspect closely potential conflicts. Areas of concern were evident in the food kiosks layout, along the proposed service road to the south, and especially in the parking lot: the lot was expanded westward and eastward, for need of additional parking spaces thereby displacing large flamboyant and palm trees in the process.

A MORE INCLUSIVE PROGRAM

We reworked with BZ Architects and the civil engineers the areas marked with red circles, with the aim of bringing new ideas for a more sustainable approach towards public space, dune and campground use, permeable ground surfaces, freshwater collection, and an overall plan for hydrological infrastructure, besides tree protection.

We noticed that the freshwater pond rehabilitation was not included in their budget, but is critical if it were to continue to receive stormwater as a program retention basin. Moreover, the proposed plant nursery was undersized and placed in a flood and mosquito prone area, while the proposed service road was attached to the boundary fence disregarding existing low grades and flooding potential. Therefore, after getting the approval of Para La Naturaleza, we started developing grading and water management design, besides dune recovery strategies, for a new, more inclusive site program.

REVISED SITE PLAN

The parking has been reconfigured and expanded. The new design incorporates all large existing trees and palms while providing stormwater management to recycle runoff water. Kiosks and administration buildings have been slightly moved to save old seagrape trees. The stage area has been expanded to accommodate the desired 250 people: it is located in a less disturbed area to the northeast of the entrance where the invasive non-native conifers of Australian pines (Casuarina equisetifolia) will be eliminated.

The plant nursery has been relocated in a more open and breezy area, with space for all infrastructure needed for a well-organized operation. A soil and composting production yard has been added. The restaurant has received a larger deck and easier, less steep access path and drive. Finally, the glamping decks are now inserted in the existing landscape taking into account views, breezes and existing vegetation.

In a low area behind the dunes that can be raised with some sand redistribution, we envision two narrow decks side by side at split levels to provide enough space for performances or wedding celebrations without damaging the plants. The dunes and their plants will move over time and may “invade” the sides of these deck platforms, partially hiding them and integrating them totally into their evolving natural landforms. The decks, in fact, will act as a sand trap and dune-building device.

PROPOSED CIRCULATION

Pedestrian and vehicular circulation are separated for safety. An 8-foot-wide walkway covered with sand is proposed parallel to the beach with a curvilinear layout to allow replenishing of the back dunes. Other smaller informal paths perpendicular to this walkway will be indicated and controlled by new signage and will direct campers and visitors to the beach. Three beach accesses will be made available for maintenance vehicles to clean the beach and move Sargasso seaweed to compost piles.

A 12-foot-wide service drive now snakes along the back south end of the site. It will be unpaved but engineered with a gravel base and side swales to keep it dry during flooding. It provides access to garbage bins and service to the maintenance buildings, propagation area, soil preparation yard, bathrooms, and the restaurant. Campers may use this small road only on the first and last days of their visit to unload and load the camping equipment they bring.

A HOLISTIC APPROACH

The Site Recovery Plan recognizes the complex dynamics of the beach ecosystem and the interdependence of biotic and abiotic components and relationships for its endurance under climatic stress. The project interventions are phased and community-driven, prioritizing the most affected areas first. Community groups will help construct, adopt and police different dune zones and different forest patches under regeneration, while growing plants in the nursery and monitoring plant growth at the same time. The learning process of producing soil, plants and water right on-site where they are needed, in an island that depends heavily and unsustainably from Puerto Rico, will empower everyone under PLN’s leadership.

The project for the site has three interrelated goals and components:

- dunes restoration

- coastal forest habitat enhancement through reforestation

- rainwater collection and stormwater management with biofiltration to create water on-site for reuse in bathrooms and irrigation.

In the restoration of dunes, forest and water systems, we seek not to “preserve” a static entity but to protect and nurture its capacity for change. Restoration thus uses the past not as a goal but as a reference for the future. Moreover, plant community dynamics and ecosystems are complex, and a successful recovery and management plan may evolve through many stages before an end result is achieved. Therefore, we recognize, with modesty, that recovery will take time, and will require a continuous involvement, assessment and monitoring.

FOREST REGENERATION

Because we cannot eliminate human disturbance in Flamenco Beach, we cannot “restore” the existing managed forest to a pre-disturbance condition. Furthermore, the uncertainty about the extent and composition of the “original” plant community at Flamenco makes “going back” to a past condition both difficult and irrelevant. By forest regeneration, we mean returning the degraded portions of the existing managed forest to a level of much higher complexity, both structurally and functionally, making it more diverse and more productive.

More specifically, our goal is to increase botanical diversity by reintroducing many important species that belong to the Dry Forest Plant Community but are now missing. Trees in the parking areas, kiosks, and campground will be selected for their capacity to be drought-tolerant, salt-tolerant, fast-growing, and shade providers. At the edge of the walkway, along the back dunes, the landscape will acquire the physiognomy of an ecotone and should be allowed to naturally develop as a hybrid between adjacencies. In periods of extreme drought, many trees will lose their leaves and go dormant as a defense. We will compost their leaves and return them to the soil to help them regenerate and awaken when the rainy season returns. We envision a rotation program for amending the existing soil, so that there will always be one or two areas fenced off from camping to allow soil regeneration.

We will not be able to replicate the complex vegetation layers, which create the vertical structure of a multi-aged coastal forest in nature, if we need to allow for passage and use by so many visitors. Only a few understory trees, shrubs, ground cover plants with leaf litter, and climbing vines would survive under the taller canopy trees with constant use by campers and beachgoers. However, native trees will be planted quite densely in all the selected reforestation patches to encourage upright growth. They will be fenced off from transit and use, for a period of time, so that the public can understand and respect the process of regeneration.

In the development of a managed forest at the edge of a beach, there is no model or project we can emulate that is applicable to our specific situation if we also want to take hurricanes’ impact into account. In the rotating patches, we will experiment with new species adaptation to specific site or storm conditions with different management parameters, which include thinning, hurricane pruning, age diversification, and density control operations, in addition to recovering soil texture and fertility. The ultimate objective of this guided regeneration process will be to study how to induce the quickest controlled growth of a robust, multi-aged native plant community with a beautifully interlocking root system able to resist with its porous mass to storm winds and adapt to future climate events, as well as campers’ impact.

There is an additional aesthetic and educational component to this proposed management method. In park design and many street replanting projects, new trees are typically planted at a distance that takes into account the size of the canopy they will eventually develop, regardless of their small initial size at planting. By following this practice, our managed forest would always feel incomplete, unfinished, and almost invisible to the eye. We do not want to keep waiting for the forest trees’ adulthood, once called “climax”; it may never occur in the way we predicted, especially under future worsening weather events. Instead, we want to enjoy and derive meaning and purpose from every phase of our forest development.

WITH TIME IN MIND

By thinning out damaged and invasive species, while introducing younger native trees, we will start creating a multi-age forest that has the capacity to better endure over time the impact of climate adversities. The young seedlings will have both sunlight and room in which to grow. Older existing trees, or short-lived, fast-growing trees, even if not botanically important, will be retained to nurse the slow-growing, shade-tolerant, but long-living, more distinguished native species, which will eventually become the site dominants.

The sheltering “cover-crop” trees may be eliminated when the newcomers are strong and big enough to support themselves against human or climatic impacts. Some may be removed naturally by future storms, as mature individuals typically suffer more mortality than younger ones. We wish to upgrade the understory as the canopy growth progresses, thinning the cover-crop species as necessary to reduce competition with the eventual dominants.

As mentioned, we will also plant trees in greater-than-ultimately-desired densities, and either thin or allow self-thinning as the forest canopy develops. A family of siblings will grow closely together in groups of different heights and ages, as it happens by natural seed dispersion, especially with parent trees, particularly in land depressions where rainwater accumulates. We will encourage mutual support of these various groups until competition and self-thinning start. Midstory and understory species may be added later. Not everything can be done and planted at once, as what was in the sun at the start will become shaded later, and what was in shade in other areas will acquire more light as the trees grow taller and taller. We want to render the evolution of this landscape legible, functional, and also beautiful, with time (and hurricanes) in mind.

Its primary role is public education. If people learn how plant communities grow and adapt, there should be no “I can’t do it” to discourage us from learning a little. It will be rewarding to engage even the environmentally minded tourists in this endeavor, as many have already expressed interest in participating. Reforestation will be managed and displayed in a series of identifiable steps, a succession of stages: each year, some areas will be fenced off for soil amendment, planting, and a decision made for its short- and long-term goals. Guiding growth in a plant community while preparing for a storm response is just like growing and watching a family evolve during a lifetime: affection and care are not sufficient without all possible precautions and measures for the safety and welfare of all family members.

RECOVERY PLAN

Category five hurricanes like Irma and María have taught us that we cannot isolate discrete portions of our landscape and socio-ecological systems to prepare and respond to climate change impacts. There is a self-similarity of scales in these systems — their structure, functions, and dynamics — from macroscale to local scale to microscale. Everything is interrelated.

Waste is output and input for the biogeochemical cycles. The shifting sand dune, the physiology of plants, the biochemistry of soil, the fluctuation of wetland salt and water, the disruption and regeneration of a forest: these are processes of the same ecosystem, interconnected forces interacting with unique, self-sustaining dynamics.

They all have the capacity to absorb stresses and maintain function in the face of climate change, working in conjunction with one another. We cannot examine or intervene at one level without affecting or remediating another. Therefore, to achieve climate resilience, we need to look beyond the limited boundary of our project site, beyond the narrow scope of a single design problem, and between the interfaces of fields of thought. The spatial scale of operations for adaptation planning is systemic, and the initiatives addressing global warming impacts cannot be myopic or confined, even within the limited resources at hand in a small island like Culebra. In a still fairly pristine environment like Flamenco Beach, we cannot propose the construction of artificial reefs, groins, seawalls, breakwaters, and other massive storm surge barriers.

AFTERWARD

We are convinced that the right approach to coastal protection for Flamenco Beach is an integrated system of discrete, specific initiatives in costal forest regeneration, water collection and reuse, integrated flood protection, and dunes recovery. It is a multilayered approach that involves resiliency measures for the new building facilities and the construction of critical infrastructure. Education is another important component. With this strategic approach, we can achieve immediate storm protection, flood mitigation, shoreline stabilization, erosion control, retention of nutrients and sediment, and, hopefully, restore habitat and food resources for resident and migratory birds. Culebra’s economy will be able to bounce back, even better than before, if the whole community becomes involved in this project, and everyone on the island understands it is a long-term commitment, not a short-term fix.

We believe that ours will be a successful model that can be replicable to other Caribbean coastal areas threatened by extreme weather events. Flamenco Beach is an ideal place to showcase remediation techniques for green infrastructure and water reuse in a dry coastal island setting. In fact, it includes the complete range of interdependent coastal habitats: fringing coral reef, beach, dunes, wetland, coastal forest. The project activities could contribute to current plans and strategies focusing on habitat and fish and wildlife restoration. These include NOAA Coastal Zone Management Program; NOAA Habitat Blueprint Focus Area: Northeast Corridor and Culebra Island, PR’s DNER; PR’s Recovery Plan; USFWS Coastal Zone and Sand Dunes Restoration Initiative; USFWS Fish and Aquatic Conservation Initiative; and USFWS Endangered Species Program Recovery Initiatives. In our desire to see this effort implemented, we wish to reach out and grow the number of Partners and Sponsors that may embrace our efforts and support the project’s implementation.

Beside these planning studies, we produced project design in plans and details for construction of the "needle" deck platforms, wood bridges, bioretention beds, and re-planting for all phased areas of the site. The buildings have been reconstructed but the site recovery implementation is on hold until sufficient funds for construction are secured.

All Photographs © Rossana Vaccarino Except Where Noted.

Printed On: June 26 2019

Printed At: Doubledey, San Juan, Puerto Rico

© All Rights Reserved. No Part Of This Publication. Total Or Partial, May Be Reproduced, Distributed, Or Transmitted In Any Form Or By Any Means. Including Photocopying, Recording, Electronic Or Mechanical Methods Or Other Means Is Strictly Prohibited Without Written Permission.