DUNES RECONSTRUCTION

FLAMENCO BEACH, CULEBRA, PUERTO RICO

PROJECT STATUS | IN PROGRESS

PROJECT BACKGROUND

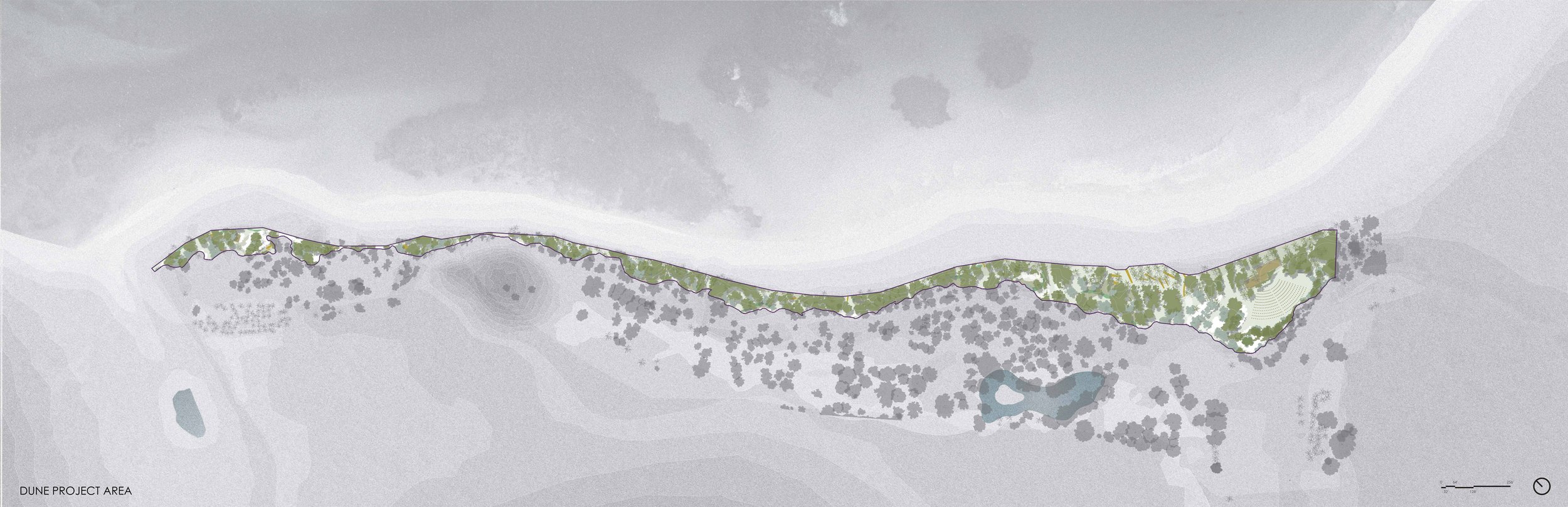

The Flamenco Beach Recovery Project is an interdisciplinary and collaborative initiative born in response to the devastation of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. Designed as a replicable model, it integrates the local community into the rehabilitation and long-term stewardship of coastal forests, dunes, and freshwater systems, while fostering conservation practices such as water reuse and green infrastructure. This section highlights the dune restoration component within a broader, threefold recovery strategy.

As prime consultant to Para la Naturaleza, Vaccarino Associates developed a five-pronged approach to guide the recovery:

Coastal reforestation with native and endemic species to replace those lost.

Habitat rehabilitation of forest, dunes, and freshwater ponds in a highly visible area that also supports recreation and education.

Entrepreneurship opportunities in Culebra that link local economies with habitat conservation and resilience.

Community participation in recovery, maintenance, and long-term monitoring to build ownership and stewardship.

Mitigation planning to prepare for future climate events through adaptive strategies and visitor/resident guidelines.

AN IMPERMANENT LANDSCAPE

Coastal dunes are dynamic, living systems that protect beaches and backshore environments. Acting as natural shock absorbers, they store sand under normal conditions and release it during storms, buffering against flooding while replenishing the beach. Their formation and stability depend on vegetation, which traps wind-blown sand and anchors the shifting landscape.

Without vegetation, dunes are highly vulnerable to the same forces that create them—wind and waves. Sand is continually shifted among offshore bars, tidal zones, the back beach, and dunes themselves. During storm events, waves drive sand offshore into storm bars that dissipate energy and reduce erosion. Prolonged or severe storms, however, transport sand even farther, gradually reshaping the beach until a new equilibrium is reached. This perpetual cycle of erosion and deposition defines the impermanent nature of dunes: a landscape in constant motion, where presence and absence are determined by changing conditions.

A RELENTLESS PERSISTENCE

Although beach shorelines and dune profiles are constantly shifting, many plant species have evolved to thrive in these unstable, salt- and wind-swept conditions. Their resilience allows dunes to persist, even as the landscape itself is in perpetual motion.

In Flamenco, dune vegetation includes Canavalia rosea, Ipomea pes-caprae, Sesuvium portulacastrum, Cakile lanceolata, Scaevola plumieri, Batis maritima, Suriana maritima, Ernodea littoralis, Hymenocallis latifolia, and a variety of grasses. Many grasses send deep vertical roots that grow in tandem with the dune’s shifting sands, while others spread horizontally through stolons and rhizomes that store nutrients and bind the surface. Together, these plants act as a smooth, adaptable infrastructure—formless yet enduring—that stabilizes the dunes and enables regeneration. Even when the surface is swept away, the underground networks remain like a hidden aquifer, sustaining life and ensuring the dunes’ return.

THE SHAPE OF EROSION

Dune vegetation not only withstands shifting sands but actively shapes them, slowing wind, trapping particles, and accumulating sand around their stems. Over time, this process builds dune mass, with plants near the ocean playing a vital role in reducing wind velocity and keeping sand anchored at the beach’s edge.

DUNES BEFORE AND AFTER IRMA AND MARIA

Before Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck in 2017, Flamenco Beach’s dunes were defined by a continuous cover of lush vegetation. In 2004, both the frontal and back dunes were almost entirely stabilized by dense plant communities, with only narrow openings for pedestrian access to the beach. The hurricanes, however, caused widespread collapse of this system, stripping vegetation and leaving exposed scarps and blowouts.

The front dunes—before Maria—had been anchored by resilient herbaceous plants, vines, and grasses, especially Ipomea pes-caprae, adapted to withstand salt spray and direct exposure. Behind them, the more sheltered back dunes supported a richer mix of shrubs such as Coccoloba uvifera, along with trees, vines, and grasses. After the hurricanes, much of this stability was lost across Zones B through H. Recovery will be slow, relying on waves to gradually return sand from offshore deposits to the beach, where wind and vegetation can once again rebuild the dunes.

CARRYING CAPACITY

At Flamenco Beach, most visitors seek shade and views from the crest of the front dune, a habit that has grown since hurricanes cleared much of the vegetation. This activity damages exposed roots and eroded embankments, while litter and daily wear compound the impact. To ensure long-term resilience, a system must be established to restrict access to the most sensitive dune areas, protecting them before restoration begins while still keeping the beach open to the public.

DO WE HAVE TIME TO WAIT?

With climate change intensifying storms, raising sea levels, and compounding visitor impacts on fragile dunes, the question arises: can we rely solely on slow natural processes of wind, waves, and plants to rebuild Flamenco Beach?

The risk is clear—another storm could strip away what remains of the dunes, our last natural reservoir of sand. While hurricanes cannot be prevented, proactive strategies can reduce vulnerability and accelerate recovery. Regenerative design, continuous monitoring, and adaptive management systems are essential to ensure that restoration keeps pace with escalating climate pressures.

CONTROLLING ACCESS

Unregulated pathways across Flamenco’s dunes accelerate erosion and damage vegetation. To protect these fragile systems, access must be consolidated, clearly defined, and managed through designed infrastructure.

We recommend closing three unauthorized access points created by storms or foot traffic, while regulating all others with signage, rope railings, and wooden dune walkovers. These walkways would act as bridges, protecting vegetation by channeling movement above or around the dunes. Less-frequented entries can use narrower, less intrusive structures to minimize visual impact. Access points 14, 12, and 8 should remain open for maintenance vehicles, as they align with existing blowout areas, but should be reinforced with angled erosion-control devices that stabilize sand without blocking passage.

STITCHING THE DUNES IN TIME

The dune system cannot be restored all at once, nor recreated in a fixed historical form—it is a landscape of constant change. What is possible, however, is a framework of careful, incremental interventions that accelerate the healing of eroded scarps while respecting the dunes’ shifting character.

Design strategies may take the form of temporary insertions—like needles that serve a purpose and withstand abuse—or natural cues, like driftwood bars caught in the dunes, guiding whether one may pass or must stay back. Walkovers and elevated platforms can double as seating or gathering spaces, designed to blend into the landscape rather than dominate it. These structures, built of wood and scaled for flexibility, would appear to float lightly above the vegetation, like rafts drifting across the dune system. Subtle, functional, and responsive, they would act as catalysts for regeneration while protecting sensitive habitats.

WORKING WITH THE WIND

Dunes exist in dialogue with turbulence—shaped by shifting winds, never fixed, always in motion. While they cannot be controlled, they can be guided: devices and interventions can channel wind currents to influence dune growth and form, creating ephemeral landscapes where nature and design meet.

Like silt settling behind walls in a streambed, wind can be directed to sculpt new curves of sand, forming intimate and unpredictable places. Our goal is to help people embrace this instability, to see the dunes’ fragility and energy as part of their beauty. Community involvement is central: volunteers rebuilding sections of the 800-foot eroded scarp would also adopt, monitor, and protect their zone. By dividing the work into smaller, visible projects, the effort becomes more manageable, personal, and educational—transforming restoration into a shared experience of stewardship.

FENCES FOR SAND TO TRESPASS

Sand fences are not barriers but porous filters—temporary instruments that mimic the role of plant stems in slowing wind and capturing sand. Their lightweight, widely spaced wood slats reduce wind velocity just enough for sand to settle, helping dunes rebuild faster while also shielding newly planted grasses from trampling. Easy to construct, they invite hands-on participation from volunteers and community groups.

Fences are placed on the seaward side of the dune, 8–10 feet from the scarp depending on conditions, and oriented perpendicular to the prevailing wind. Laid out in 100-foot sections with periodic gaps, they avoid trapping storm surge or rainwater. If needed, a second tier can be added to increase dune height and fill valleys between existing and new dunes. Eroding scarps and exposed roots can also be stabilized with dry Sargasso algae, twigs, and organic matter that decompose as sand accumulates, creating the soil base for new roots. Complementary dune walkovers—2.5 to 5 feet wide, with railings and angled to the wind—would guide pedestrian access while allowing dunes and vegetation to grow naturally beneath.

EROSION AND DEPOSITION

At Flamenco Beach, back dunes have lost both sand and organic matter, much of it displaced onto paths and campgrounds. Restoration can begin by raking sand back into the dune zone with proper organic amendment, forming low, stable dunes that never exceed four feet in height or the natural angle of repose. Community participation, through simple sand-fence installation, will make the effort accessible and collaborative.

Volunteer maintenance and monitoring will be guided by clear protocols, ensuring that problems are addressed while also welcoming naturally arriving species into the mix. Unlike a static garden, these dunes will evolve over time, embodying resilience rather than control. Integrated with the reconstruction of the walkway, the project will allow visitors to experience dune vegetation up close as they head toward the campground, bathrooms, or food kiosks. For those directly involved in planting, the growth of these living systems can foster not only ecological awareness but also a deeper emotional connection to the landscape.

WEIRS FOR A FLUID LANDSCAPE

The back dunes should not be reconstructed as fixed forms but allowed to remain dynamic, alive, and in constant motion. Our approach is to guide this natural self-organization through “ribbons” of vegetation that function like weirs—partially holding sand in place while still allowing movement and transformation.

These vegetated weirs would act as subtle counterpoints, protecting sand during storms while making the dunes’ shifting contours more legible in calmer weather. Their flowing lines would echo the rhythm of wooden walkovers and splinter-like structures that both mark and heal pedestrian scars in the landscape. Immersed in this setting, visitors would experience the dunes as a living flux—like drifting wood caught in currents—returning slowly to the shore, and returning home.

UMBRELLAS FOR SHADE

To reduce trampling of dune vegetation and damage to exposed palm and sea grape roots, we propose introducing rental beach umbrellas, as is common in managed beaches worldwide. By drawing visitors closer to the shoreline, umbrellas would provide shade while relieving pressure on sensitive dune zones. In high-use areas, wood platforms could also be installed at the dune crest for seating or rental, generating income while rope fencing directs foot traffic to designated deck areas, minimizing compaction and erosion.

AFTERWARDS

Dune rehabilitation forms a critical component of the threefold strategy for the Flamenco Beach Recovery Project. Click through for more information on the complementary Coastal Reforestation and Water Infrastructure recovery initiatives.

Alongside these planning studies, we prepared detailed designs for the site, including “needle” deck platforms, wooden bridges, bioretention beds, and phased replanting strategies. While building reconstruction has been completed, site recovery remains on hold until sufficient construction funds are secured.

All Photographs © Rossana Vaccarino Except Where Noted.

Printed On: June 26 2019

Printed At: Doubledey, San Juan, Puerto Rico

© All Rights Reserved. No Part Of This Publication. Total Or Partial, May Be Reproduced, Distributed, Or Transmitted In Any Form Or By Any Means. Including Photocopying, Recording, Electronic Or Mechanical Methods Or Other Means Is Strictly Prohibited Without Written Permission.