THE ARBORETUM

ST. THOMAS, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS

PROJECT STATUS |COMPLETED

PROJECT BACKGROUND

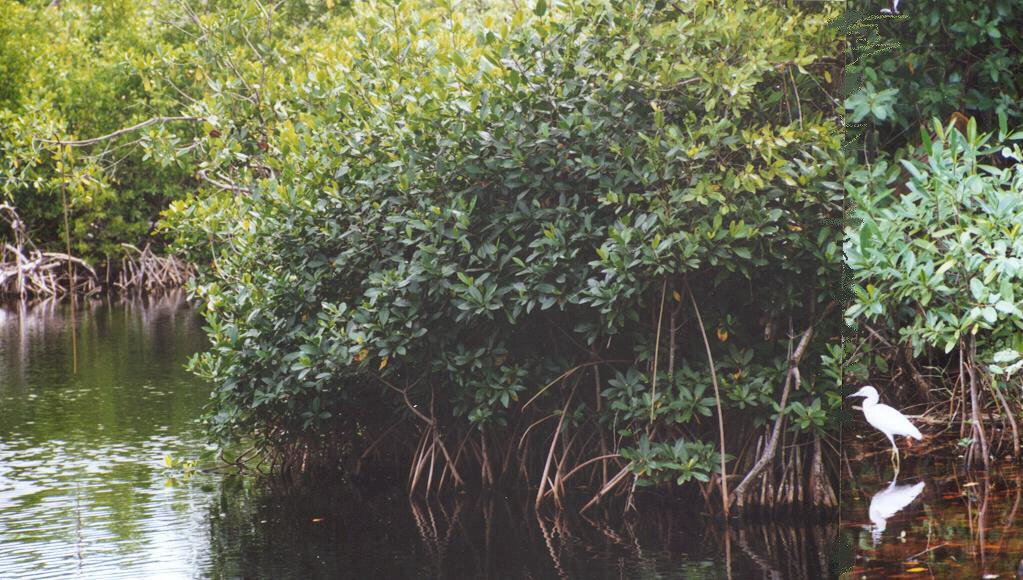

In June 2003, the Magens Bay Authority (MBA) decided to “restore” the Arboretum at Magens Bay and hired us to guide them in this effort. We proposed preliminary planning work that included in-depth historical research, a tree inventory, and site analysis to help understand and reinterpret the spirit of the earlier tree collection, while promoting a new mission and programmatic strategies more aligned with our times. Our goal was to help develop and convey new meanings, as well as stronger educational and recreational opportunities.

Some of the investigations and recommendations shown here were part of a preliminary report and planning studies we prepared for MBA to secure substantial funding sources necessary to produce a Framework Plan and cover some of the reconstruction costs. We hoped to help stakeholders reach consensus for the implementation of both the Framework Plan and the proposed phased projects, ensuring knowledge transfer, community outreach, and research opportunities. However, the project was not implemented. In 2017, Hurricane Irma greatly damaged what was left of the plant collection and the beach as a whole. The "old palm" and "tall coconut grove" were wiped away, along with many of the large mahogany and seagrape trees on the beach.

THE SITE

The Magens Bay Arboretum has evolved from the original formal gardens of the 1920s-40s to the present-day semi-wild garden habitat, encompassing a diversity of exotic and indigenous species, birds, and other types of wildlife. The site is located at the southwest end of Magens Bay, at the bottom of an ecologically sensitive watershed that also includes the most important and largest archaeological sites in the northern Virgin Islands, all concentrated around the beach area. Magens Bay Beach Park, with its grass, trees, and coconut grove plantation, is the most popular open space in St. Thomas. Both residents and visitors gather for recreation and special events at what National Geographic once called “one of the ten most beautiful beaches in the world.”

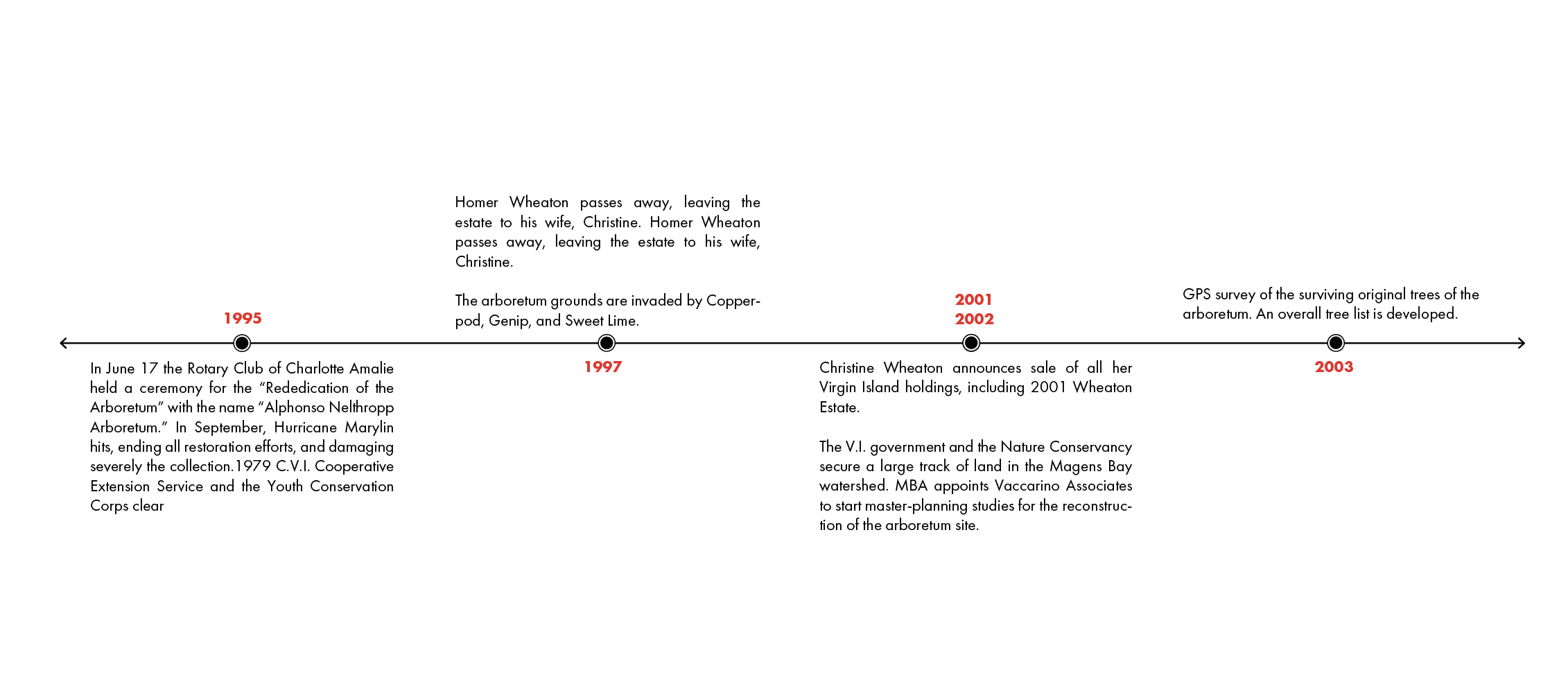

The Arboretum, hidden from view and use, is largely forgotten by the people of the Virgin Islands. It is in a state of abandonment and in desperate need of a new identity. Many of the existing land-use challenges from twenty years ago, when we did this study, remain the same or have worsened due to the impact of hurricanes, increased numbers of visitors, and improper replanting or maintenance practices. Sporadic interventions and capital investments have proven unsuccessful without a Framework Plan and a management strategy that embraces the whole of Magens Bay, guiding and regulating resource use in the long term, project phasing, maintenance, and fund allocation.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

We did extensive research to trace the history of the arboretum and its site, but the long timeline (starting in B.C.) now should be extended from the date we completed this work.

SOIL EROSION

Most of the land on both arms of the bay has been subdivided into lots one acre or less. Clearing for residential development and cut/fill operations have created topsoil erosion and sediment runoff into the bay. This problem has escalated in the last 40 years on the sides and the upper reaches of the Magen’s Bay watershed, with changes in the distribution of the of the soil, which, in turn, has changed the flora and fauna of both terrestrial habitats and marine environment. The Arboretum and the Magens Bay plant communities hold water and soil and should be protected to prevent topsoil loss and sedimentation into the ocean.

SEPTIC EFFLUENT AND POLLUTION OF THE BAY

The upland soils at Magens Bay are shallow with bedrock near the surface. Shallow soils and steepness of slope are serious limitation for septic tanks filter fields. During periods of heavy rainfall, the soil becomes quickly saturated, resulting in the surfacing of septic effluent and the possibility of contamination in down-grade cisterns and of the bay, killing the juvenile fish that was once so abundant. The well and other water sources in the Arboretum as well as the septic system from the bath houses should be tested regularly for volatile organic compounds and salinity before being discharged into the ocean or used for irrigation.

For years the U.S. Virgin Islands has struggled with wastewater runoff issues that threaten human and environmental health. The problem is difficult to miss, since it’s highly visible after every heavy rainfall: A murky, brown ring outlines the islands from the sediments and pollutants that wastewater runoff, including stormwater, carries down the slopes. It’s not uncommon for the V.I. Department of Planning and Natural Resources to issue advisories that caution against swimming and fishing at beaches at which too high a level of enterococci bacteria levels has been found.

RECREATION IMPACT

Magen’s Bay accommodates many community gatherings and special events for music, sports, religious and civic functions. Overnight and day camps are allowed, and the Boy Scouts gather and train in the Arboretum 8-10 times a year, with groups ranging from 25 to 200 people. Commercial activities catering to the tourism industry and marine-based activities are another source of stress. A study on the carrying capacity of the beach and its facilities should be done to evaluate existing and future uses and their impact on existing infrastructure and land/water resources.

Boy scouts’ campfires and camping under Arboretum trees are a threat to the survival of the surviving tree collection. Parking under old mahogany trees is not sustainable for a heavy use of the beach, damaging the roots of the trees and increasing the discharge in the ocean of pollutants from automobiles. Parking and vehicular access should be relocated behind these trees for safer pedestrian use of the beach and for jogging and picnicking.

DEGRADATION & ABANDONMENT

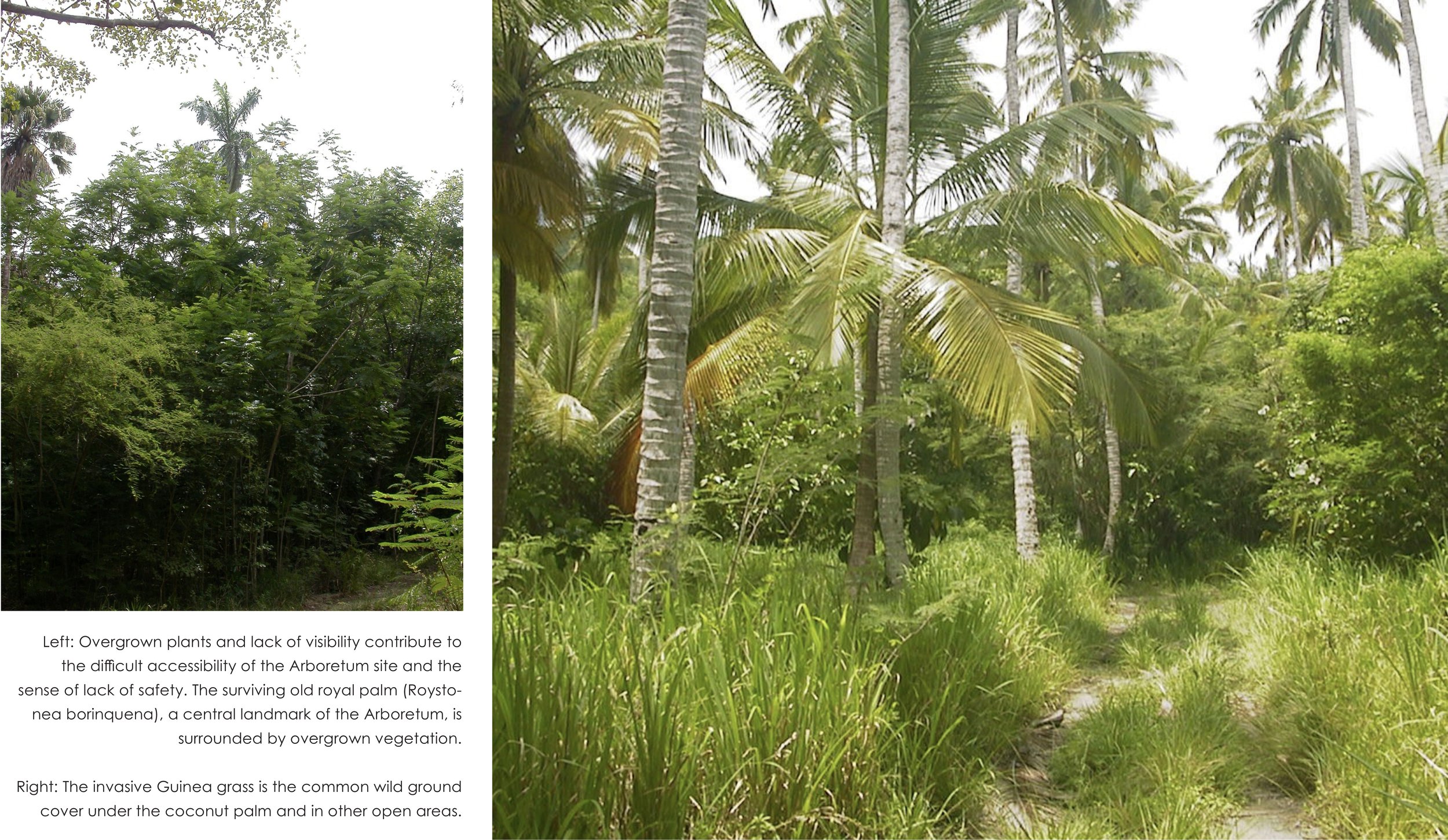

Non-native plant species, such as sweet lime, copper-pod, and genip are invading the Arboretum ground for changed conditions of light and canopy cover after hurricane storms and maintenance clearing. These species have for years affected the remaining existing tree collection and the possibility to grow other trees.

The whole southwest end of the floodplain by the beach and the Arboretum is an archeologically sensitive area, as it was part of an historic plantation. A pre-ceramic archaeological site has been found with indications of past human activity. Piecemeal cleaning and clearing activities must be prohibited until a plan is in place. The effort of getting rid of invasive species to re-open the Arboretum site to potential users can be more more damaging than leaving the site as is if it is not professionally guided. Maintenance crews need to be educated. Funds for a long-term maintenance and management plan should be secured before any new clearing or replanting is done. Stakeholders need to tap into private sponsors to integrate the limited public funds available.

LAND USE CONFLICTS: VEHICULAR VS. PEDESTRIAN TRAFFIC

Major conflicts are at Magens Bay entrance, concession buildings and around the picnic sheds. Vehicular access needs to be prohibited in the Arboretum and Magens Bay trails (except for maintenance and emergency vehicles) to prevent root system damage and soil compaction. This is specially important because the Arboretum currently does not have pathways. A new road has been built since this report was presented without considering a better location to avoid conflicts with pedestrian use.

LAND USE CONFLICTS: ACTIVITIES VS. PASSIVE RECREATION

Many visitors go to Magens Bay for relaxation and for its scenic beauty. Excessive noise from high-powered stereo systems during beach parties at the picnic sheds significantly reduce the recreational experience for most beachgoers and will interfere with the educational goals of the Arboretum, should the Arboretum be restored to its function. Provision for additional single-interest groups should be discouraged at Magens Bay.

A NEW MISSION WITH GLOBAL TRENDS

Botanic gardens and arboretums have played in the past a significant role in the world’s economic and scientific progress --including taxonomy, horticulture, agriculture, medical studies, introduction of new plants for economic exploitation, and ornament. Today they often have become silent spectators under the different recreational and educational venues of the present-day society. Moreover, the Magen’s Bay Arboretum site is already an “open system” undergoing different cycles of succession, very much in conflict with the original notion of a delimited botanical garden to be maintained and kept fixed in a particular time in history.

Therefore, we should look at the future and define a new mission for the Arboretum that participates to global trends. The Arboretum could be not only a collection of trees from many distant places but also be the showcase of a precious and unique natural and cultural environment, to be appreciated by visitors from all over the world. The opportunities in revitalizing the site are multiple, and all should be considered: recovery of memory and production of new knowledge can both be accomplished, innovation and interpretation of a unique legacy can be featured side by side.

THE WATERSHED AS CONTEXT

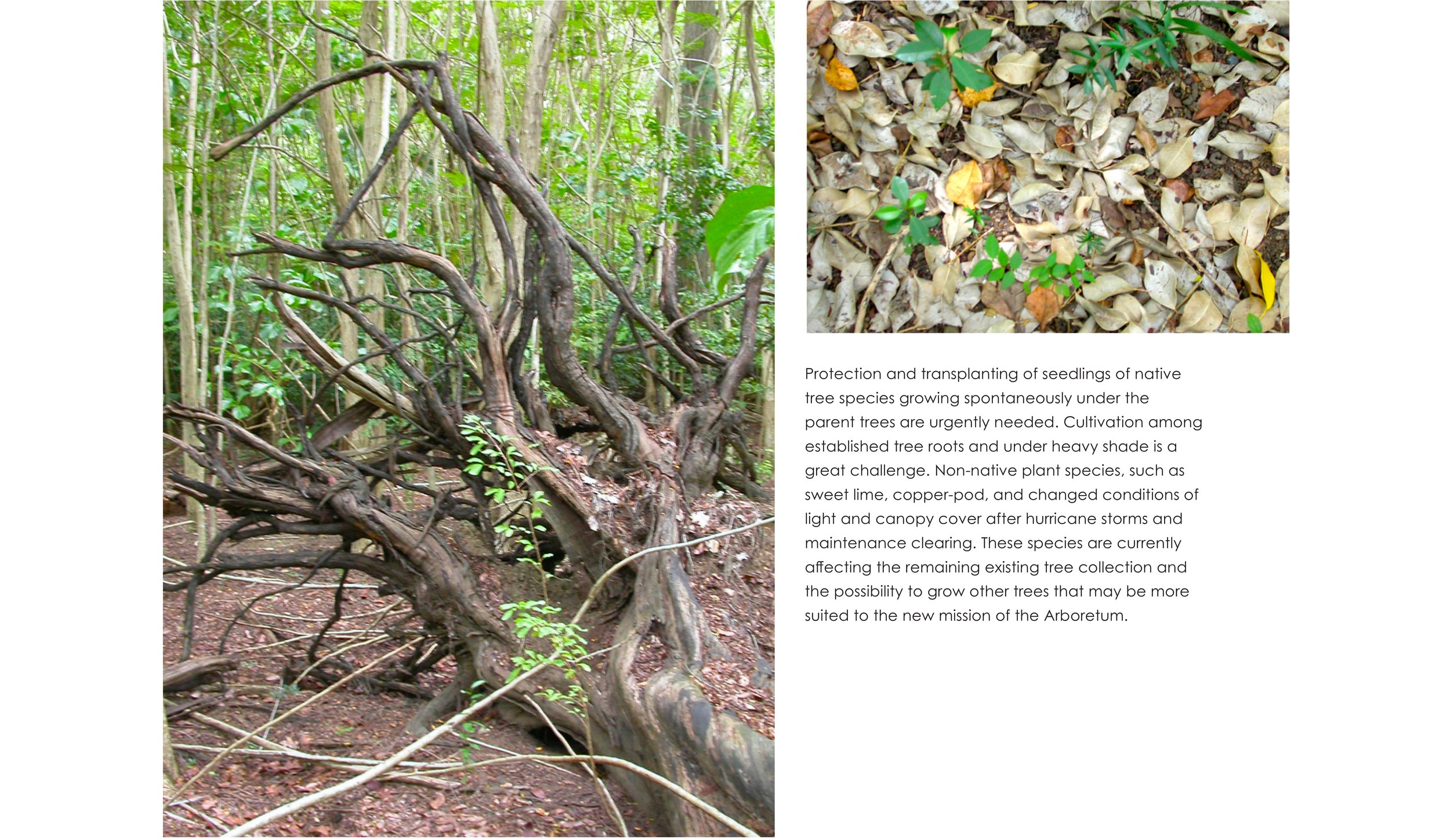

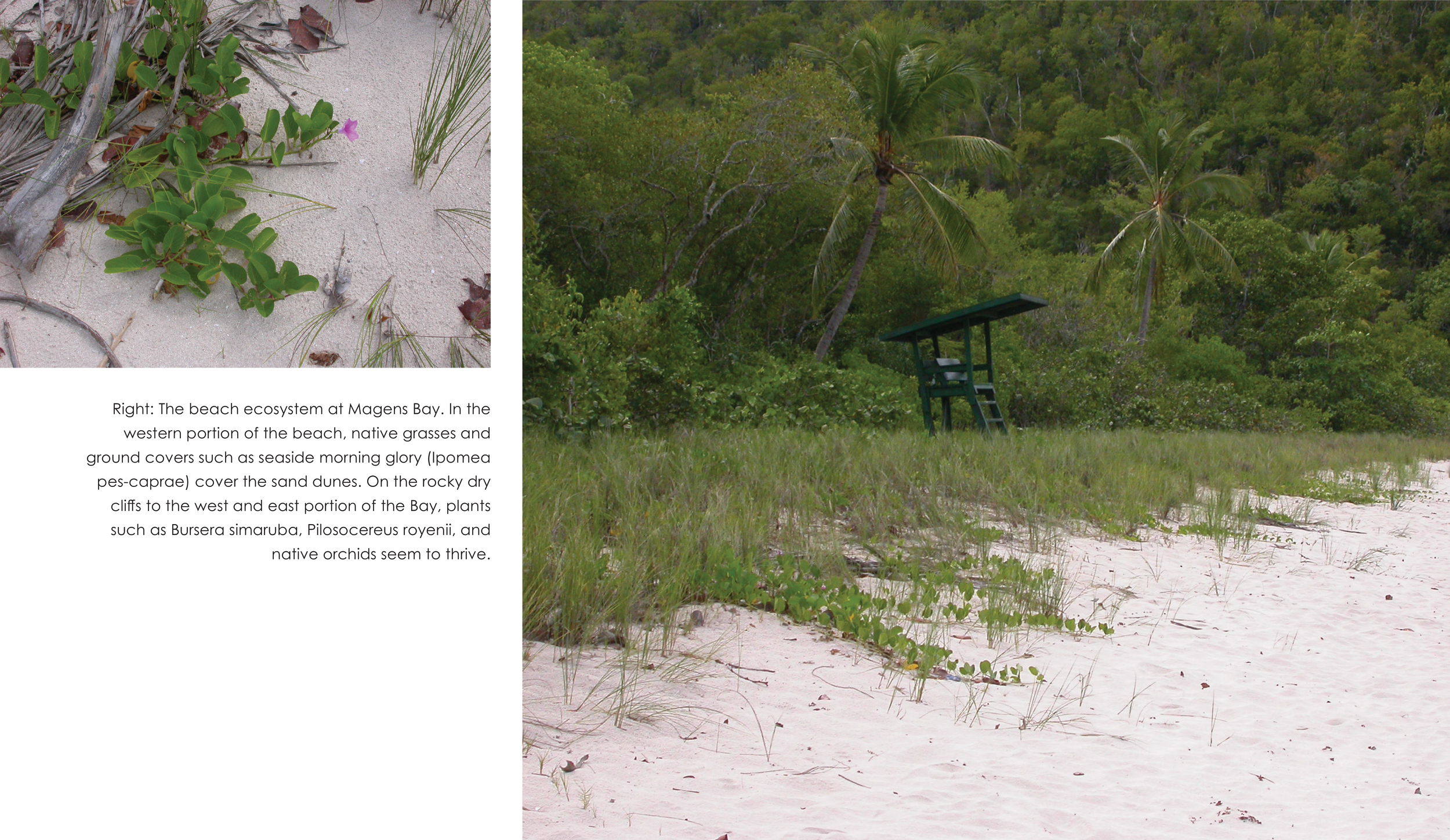

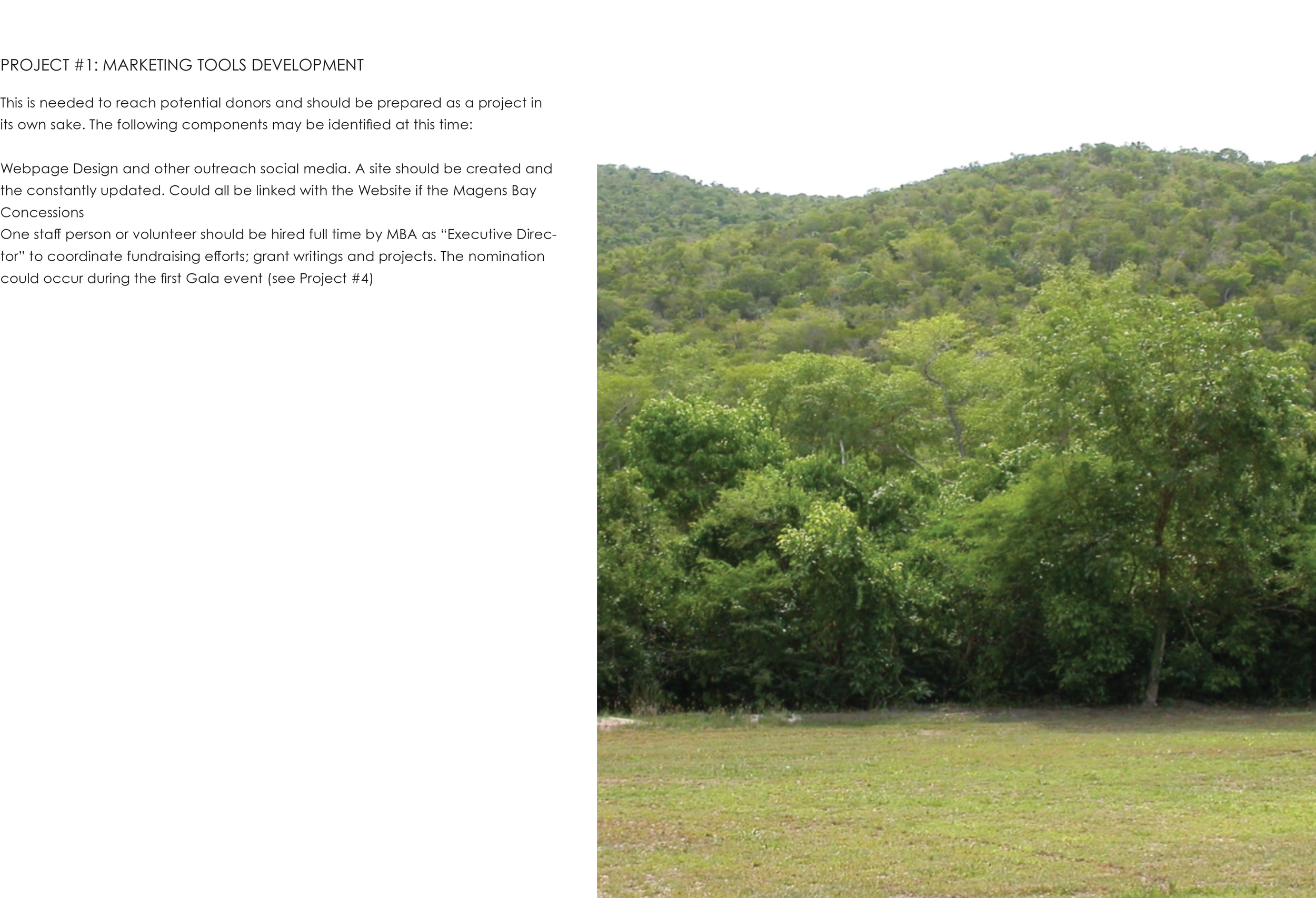

The significance of the Arboretum increases when its mission is defined within the larger framework of Magens Bay’s natural systems and cultural history. Since its creation, the Arboretum’s function and use were in fact conceived to be part of a larger landscape that included the beach and the coconut grove plantation. Representing 5.5% of the island of St. Thomas, the 1,210-acre Magens Bay Watershed, with over five miles of coastline, is characterized by a mixture of residential and commercial development, recreational usage and undisturbed 100-year-old forest, after heavy sugar cane production during the 1800s. The steeply sloped watershed, dropping from 900 feet above sea level to the sea, represents a cross section of modified but stable plant communities ranging from coastal mangroves to tropical dry and moist forests, which provide habitat to many species of endemic and migratory birds. The bay’s marine environment consists of extensive sea grass beds that provide habitat to the endangered green and hawksbill turtles. A total of eight federally and locally listed endangered species exist in the watershed and surrounding waters.

SYNERGY OF STAKEHOLDERS

The Arboretum is physically and symbolically located at the intersection of the ownership boundaries of the three Magens Bay Preserve conservation stakeholders: The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR), and Magens Bay Authority (MBA), which manages the beach facilities. Its rehabilitation is a symbol of a needed focus into a common planning effort for Magens Bay, where each party can play a specific role. The Nature Conservancy, working with the Virgin Islands Government, created the 319-acre Magens Bay Watershed Preserve – an undeveloped, forested preserve that drops from over 500 feet above sea level to the beach in Magens Bay. The Virgin Islands Government, with 112 acres, Magens Bay Authority, a quasi-governmental agency with 68 acres, and The Nature Conservancy with 139 acres would co-manage the Magens Bay Watershed Preserve (representing nearly 1.5% of the entire island of St. Thomas, and over 25% of the Magens Bay Watershed)

ARCHEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY IN PARALLEL

Prehistoric and colonial cultural sites have been found in almost every bay of the north shore of St. Thomas and St. John. What looks at first a natural area is instead a landscape with vestiges of ancient human land uses. Evidence of former environmental conditions and clues to past land uses lie in the archeological deposits that are are found in Magens Bay and the Arboretum site, and in the interpretation of the stratigraphy that has been exposed during archeological investigations. Images below: vestiges of an old cart road in the Arboretum and the “crater” left by a disappeared trunk of a palm.

The economic potentialities of tropical plants are still largely unrecognized and undeveloped. The richness and complexity of the tropics in plant species and plant associations represent a still inadequately investigated source of genetic material. It is also well known that tropical ecosystems are on the verge of extinction, especially in areas such as the Caribbean where development pressure and tourism are exerting a tremendous pressure.Archeological site surveys could be done simultaneously to the soil testing and botanical/ecological data collection during and after the planning studies, and should happen prior to any change or land disturbance.

THE INTEGRATION OF LEISURE AND EDUCATION

The extraordinary natural setting of Magens Bay, the beach, the Arboretum and coconut grove, make it a prime recreational area for Virgin Islanders and a key resource for the tourism industry in St. Thomas. Current trends in Eco-Tourism suggest an opportunity to increase environmental education as part of leisured activity, and nowhere else better than in the Arboretum could this challenge be met so successfully. Recreation at Magens Bay occurs primarily along the beach and in the parkland in proximity to the picnic sheds, with a concentration of visitors around the concession buildings and the equipment rental facility. A physical and programmatic expansion of educational programs in the Arboretum, the coconut palms grove and the nearby natural areas own by TNC and DPNR would, instead, create a potential overlap and interaction with leisure activities, with the enrichment of both.

WORK SIMULTANEOUSLY AT DIFFERENT SCALES

We proposed to conceive and organize interventions considering three broad realms that are influencing one another, from small to very large: the Arboretum, the Botanical park, the Ecological park.

The Arboretum would be grounded in the notion of teaching/education, accomplished primarily through exhibitions, both of designed and natural systems. These exhibits would be emotionally appealing, would vary in scale and cover two main areas:

Natural realm: exhibits of various species, plant communities, and larger ecological systems

Cultural/Historical realm: archeological findings, Arboretum/island history.

The Botanical Park would include the beach and coastal species, the parkland around the picnic areas with passive and active recreation, a restored coconut palms grove and a mangrove shrubland display. The Ecological Park would include a larger collection of plant communities in their relatively undisturbed state, along with important archeological and historical sites. Some of these plant communities could be used as “controls” by which land management programs can be judged and evaluated.

The Arboretum would continue to display trees as it once did. However, species selection would change since what was once rare or exotic may be now commonplace. And what once might have been common or unknown is perhaps today endangered. During the planning and design phase, different vegetation zones may be developed that co-exist within the Arboretum: historical (original tree specimens), endangered species, native species, and endemic plant communities. There could also be an emphasis on neglected or misunderstood native plants, such as bromeliads featured in a bromeliarium, orchids in an orchidarium, and a dry garden display with native succulents or endangered coastal plants.

CREATE A NETWORK OF TRAILS

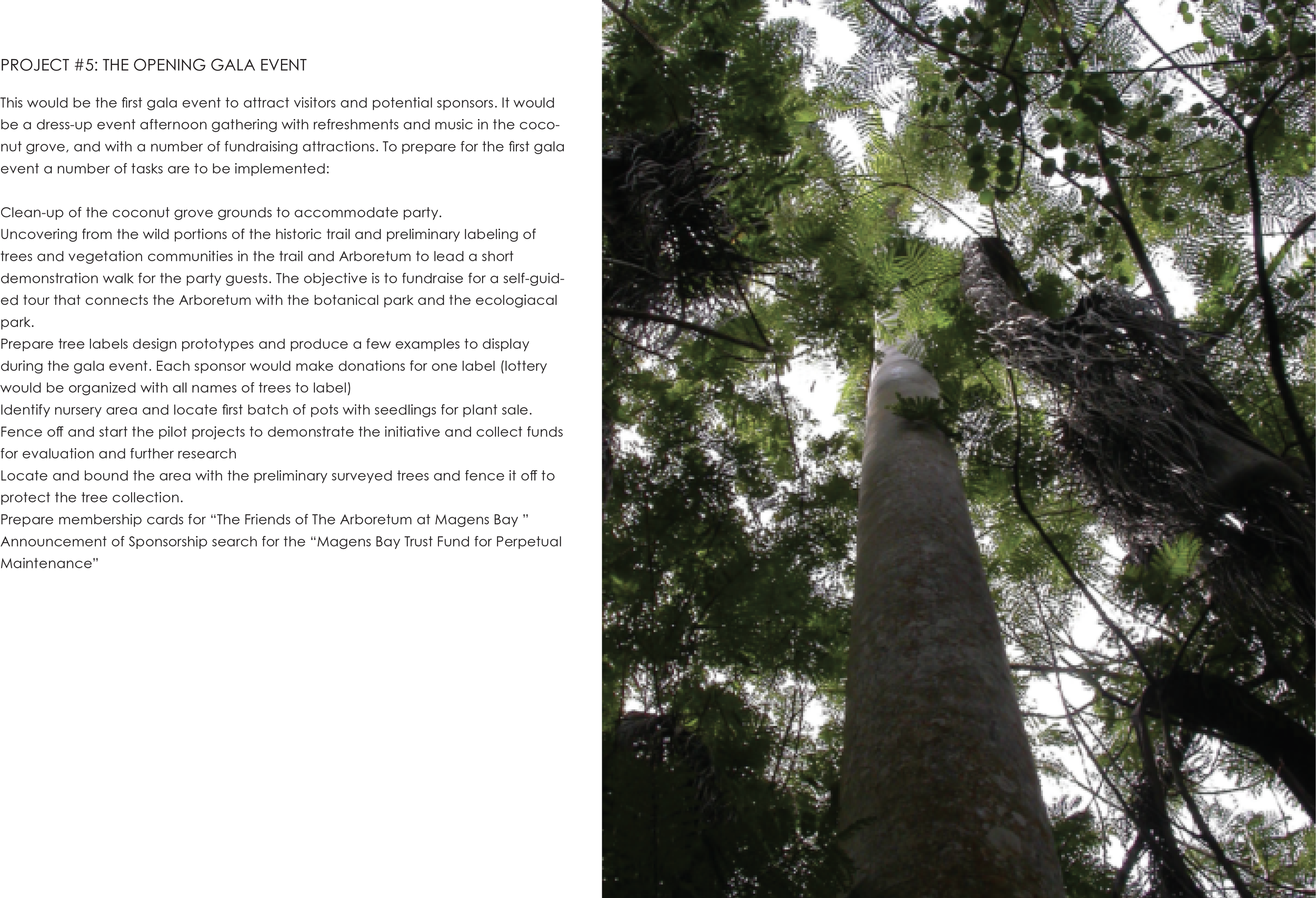

Self-guided tours of the exhibits and plant collections would provide educational and recreational experiences and could be enjoyed by hundreds of visitors every year. A system of hiking and walking trails would connect the various exhibits across the Ecological Park, connecting the more natural areas with the designed and managed zones more pertinent to the Botanical Park and Arboretum displays. The trails would also lead to a propagation/nursery/plant sale area, experimental gardens and research plots, and other programmatic elements to be designed for the park.

Recommendations:

- Diversify trail experiences (place learning stations with exhibitions along them, interpretive signs, etc.)

- Label and identify all important plant species in each ecosystem/plant community display.

- Protect and fence off all archeological sites to be still investigated

- Include information on the hydrological systems and site design systems that conserve water as part of the exhibits (the drainage system for the Arboretum, runoff water collection before discharge in Magens Bay, gray water reuse for irrigation., etc.)

- Provide security measures along the trail network.

IMPROVE CIRCULATION & PARKING

The access road would be relocated to the southeast of the picnic sheds to provide safe pedestrian accessibility to the beach and to reduce traffic congestion and to increase pedestrian safety as well. The number of private vehicles driving and parking in close proximity to the beach would be reduced and integrated by shuttle runs from key points in St. Thomas. These shuttles could be run by taxi drivers and would not compete with taxi services. They could additionally provide service to more isolated residential areas of the island that may not be able to currently reach Magens Bay with public. In these photomontages is shown the before-after condition resulting from redirecting the access road to the back of the picnic sheds.

EXPAND THE POTENTIAL OPEN SPACE

If the vehicular access is relocated to the back of the sheds, pedestrian trails or jogging paths may be established close to the beach, increasing the amount of grass and play areas for family and children in proximity to the beach. By regrading and reconstructing the road, it will be also possible to create depressions and bioswales to collect the stormwater in a natural way thereby protecting the bay from sedimentation and polluted runoff during heavy rains.

DEVELOP A FRAMEWORK PLAN

A Framework Plan would be needed , with the help of external funding, to guide and coordinate short- and long-term goals for the Magens Bay area. This plan would identify projects and their implementation sequence, new circulation systems, necessary infrastructure, and bioretention areas for flood control, as well as educational and recreational programs and new event/activity spaces. Additionally, the plan would assess the recreational needs and carrying capacity of the beach, coconut palm grove, and Arboretum areas. For the Arboretum specifically, the plan would identify plant selection and acquisition, propagation strategies, educational exhibits, and financing and management strategies.

CREATE A TRUST FUND FOR MAINTENANCE

The key to sustained programmatic success in any vegetation control and management is perpetual maintenance. Areas opened by control projects are prone to re-invasion of aggressive species. Dormant seeds viable in the seed bank can be potentially released due to the change in micro-environmental conditions. Diligent and continuous maintenance however will facilitate the reduction of time and funding required to achieve acceptable results. The “Magens Bay Trust Fund” for perpetual maintenance should be fostered at the same time of the development of the Framework Plan. It would address cleaning/repair efforts, preservation/conservation initiatives, grounds keeping methods, a pilot project for invasive tree species, and control of invasive, non-native grasses, among other short and long term initiatives.

NETWORK RESEARCH EFFORTS

Collaborate with UVI-CDC, NPS and other tropical arboreta and institutions to carry out scientific studies that shed light on the evolution of local ecosystems. Research effort should also identify, collect, document and reproduce genetic pool of wild relatives/primitive cultures almost lost for productive tropical agriculture, urban reforestation, and landscape ornament. Research and monitoring projects could be also exhibited in “experimental gardens” in the Arboretum and would help support other activities by providing the needed information about the dynamics of cultural and natural systems. The research plots and experimental gardens could be used as living laboratories for university or extension services courses and students research projects, as well as become case studies for conferences and public lecture series. With appropriate funds, the Arboretum could prepare an annual report publication that would inform the public and potential donors of its activities.

SHORT TERM INITIATIVES

These are small, tangible projects that can be carried out immediately with limited or initial funding and may set in motion reconstruction improvements before a planning and maintenance strategy has been completed.

The Coconut Grove with Cocos nucifera “Jamaican Tall” is now history

AFTERWARD

As in many public or institutional projects in the islands, the lack of funding, civic commitment, changed political power and convoluted bureaucracy are among the reasons for halting the implementation of a vision that we so passionately try to develop with our clients and local stakeholders. The lack of proper maintenance and operational management are another typical reason for an implemented landscape project to fail after its construction. To this are to be added hurricanes, which come in cycles and now stronger than before. The trees and coconut grove at Magens Bay were severely damaged in September 2017 by two category 5 Hurricanes, Irma and Maria. MBA hired a local garden center in 2018 to replant the beach with trees and coconut palms, which are not the “Jamaican Tall” species no longer cultivated, but new horticultural cultivars, that are more resistant to the Phytophtera (lethal yellowing disease) The palms were planted in a line in a very unnatural fashion, without correct soil preparation and staking, so many have been lost since then.

In the meantime, inside the Arboretum the predominance of copperpod (Peltophorum pterocarpum) has continued to increase with the further sprouting from the trunk of fallen trees, but the germination of native species continues to support the temporary competition and recovery process just as we noticed many years ago. Therefore, the issue of how to restore, what to selectively remove, and what native species to encourage or cultivate remains the same. The Arboretum is not a natural environment, but we can still assess its ecosystem services and tap into its recreational and educational value if there is public will to do so. Many of our earlier assessment and recommendations are still valid. Our research, plant inventory and site evaluation can be used in any new future studies, and we will be happy to share and participate in any new effort sponsored by the local community.