CHARLOTTE AMALIE WATERFRONT

ST. THOMAS, VIRGIN ISLANDS

PROJECT STATUS | COMPLETED

PROJECT BACKGROUND

When we ran our studio practice as Paradigm Design, our leading team consisted of four partners—Rossana Vaccarino, Torgen Johnson, Scott Natvig, and Jose Ortega. Our first project was to support local key stakeholders in their desire to develop an urban design strategy that would counter the proposal of expanding the four-lane highway corridor planned along the harbor and waterfront edge from Long Bay to the Historic District in Charlotte Amalie.

The intent was to address the community concerns for traffic congestion, to be solved in their mind by building more road capacity. We suggested that transportation systems in our tiny islands needed to be thought of as an integral part of our open space and tourism infrastructure. We explained that road design could incorporate a much wider set of goals going beyond the sole purpose of alleviating traffic problems: it would include access for all, community identity, storm surge awareness, and civic investment.

Our traffic corridors could indeed be boulevards or avenues if large trees and palms were incorporated in the design, making them more appropriate to the island cultural heritage and urban revitalization needs. We proposed a multimodal transportation system that was reusing the historic waterfront without more road paving, positively shaping future urban form and human experience.

It included a pedestrian esplanade across the entire harbor’s edge, with water ferries, rather than taxi-only, connecting the Historic District to the airport, the cruise ship docks, and other parts of the island. Traffic calming measures included a comprehensive parking, taxi, and traffic management plan for downtown. Our proposal was the winner in the V.I. Port Authority competition organized in 1999-2000.

VOICING COMMUNITY CONCERNS

Before the competition entry, we engaged representatives from Port Authority, government officials, NGOs, business owners, and community leaders in a number of meetings and workshops to listen to their concerns. We also embraced the role of educators, explaining that the federal funds available for road expansion could be used with a green infrastructure and urban revitalization approach that would also benefit pedestrian use and safe crossing, along with pollution, noise, and flood control, diversity of land use, and services provided to benefit all, not just the day visitors.

It seemed that nobody was sure they wanted a four-lane highway wrapping around the historic harbor but could not envision alternatives to solve the traffic congestion. Years later, with the office of Vaccarino Associates, we continued to prepare presentations to the Governor and key stakeholders on behalf of the Charlotte Amalie Task Force, to steer political support for a more comprehensive redevelopment and revitalization strategy. We advocated for the creation of a strategic plan that would identify, organize, and integrate a sequence of actions or projects that would affect positive change for the town as a whole.

BRINGING PEOPLE TO THE WATER’S EDGE

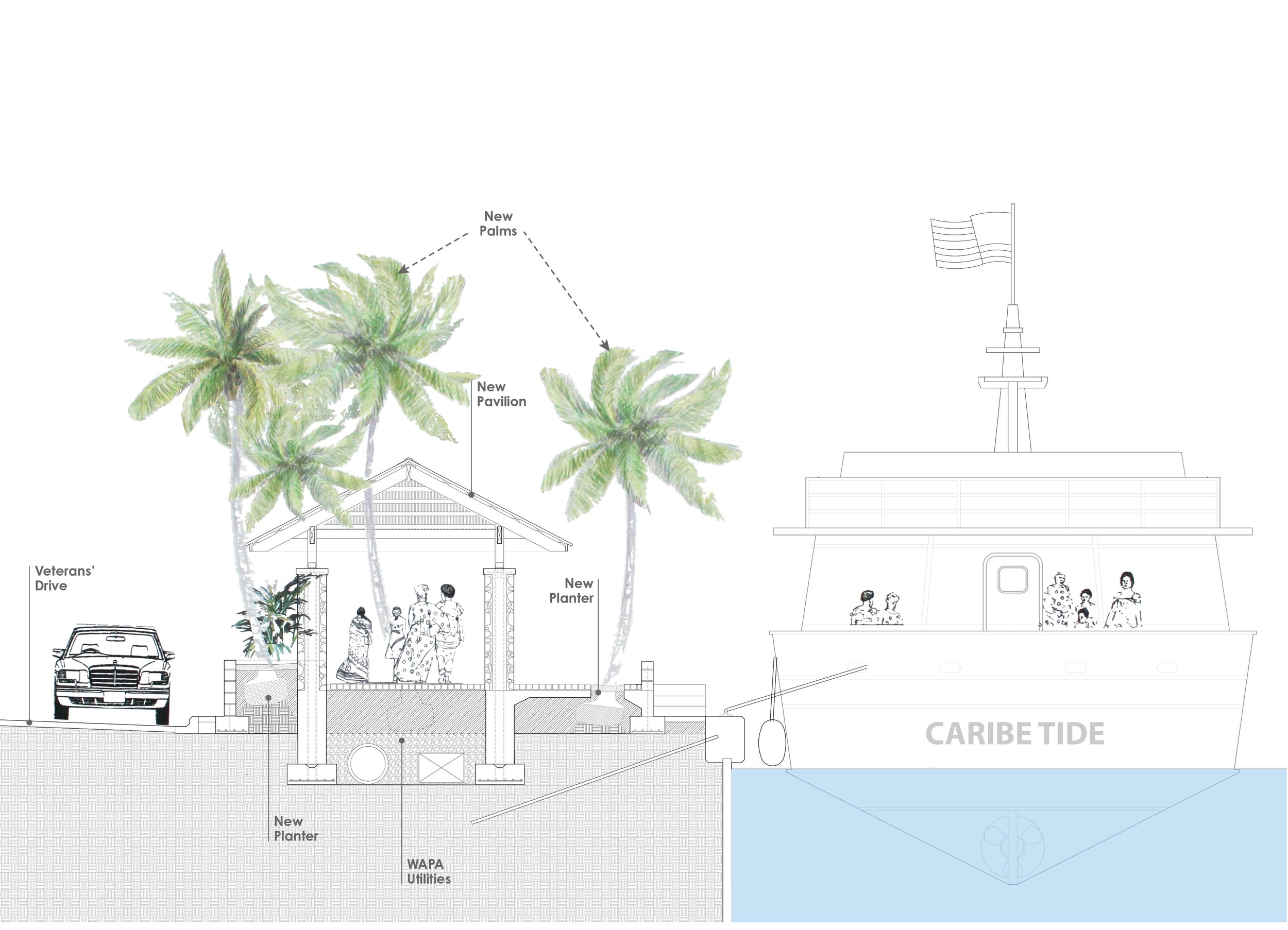

To address the specific brief and limited budget of the competition entry, we redesigned the most important traffic intersections with trees, lighting, furnishings, ferry and bus stop waiting areas, and other amenities, plus the storefront sidewalks along Veterans Drive that lacked shade and shelter from the four-lane highway noise and pollution. Our goal was to slow traffic to allow safe pedestrian use and to strengthen the original connection between the district and its waterfront activities. We presented three concept alternatives to choose from for one of the water ferry stop waiting areas.

Soil engineering, drainage, and appropriate root volume space were proposed underneath the concrete paving of the waterfront apron, necessary for the long-term growth of canopy trees and large coconut palm trees typical of our beaches. The decked concrete area of the apron would allow the various uses of the waterfront, including pedestrian traffic, yacht mooring, cross-island ferry mooring, and harbor unloading and loading of goods. The paving would protect the planting soil from erosion caused by strong waves from hurricanes.

The coconut palms used throughout the proposal are a symbol of the wet tropics, not the desert Phoenix sylvestris palms that are currently used and overused everywhere in the islands. Our planting strategy was a reaction to the local practice of planting trees in fill or rubble left from highway construction in narrow medians or tree pits, which has proven to be a failure and a total waste of money.

Bringing people to the waterfront by ferry from the cruise ship pier was a key component in the strategy to decrease vehicular traffic, which is, for the most part, created by visitors arriving by the thousands every day. We all knew that moving around by taxi in our road system is stressful for visitors and unattractive.

On the contrary, it is spectacular to arrive by ferry, whether from the cruise ship dock, the airport, or other island locations. From the ocean, it is still possible to appreciate from afar the overall morphology of the century-old capital with its unique architecture, small-scale buildings, narrow streets, and unique stepped streets climbing up the steep topography.

Upon landing on our roads or the concrete apron of our waterfront, up close, the reality our visitors face is quite different. The complete lack of vegetation, shade, and amenities, and the jewelry and souvenir shops occupying most of the real estate, make people wonder— “Where is the American tropical paradise? Where is the quaint historic district?”

AFTERWARDS

Our proposal for the Charlotte Amalie waterfront competition here shown in plans and models is now 25 years old, and was only appropriate for its time and limited budget. It was not built.

Since then, a four-lane highway expansion has been constructed in the harbor from Long Bay to the two-lane bottleneck that exists between the Fort and Capitol Building. The few trees and palms planted are slowly deteriorating in the narrow medians or pits with no proper soil, failing pedestrian use because of lack of shade along the water’s edge. The community is getting ready now to complete the four-lane highway connection to Charlotte Amalie, filling the waterfront edge around the Capitol Building.

Today, however, our worldwide priorities on urban waterfront rehabilitation have changed. Besides bringing people to the water’s edge with linear parks, there is the additional challenge of protecting communities from sea level rise and other harsh climate events, such as tsunamis and strong hurricanes.

Today, our built environment and important infrastructure, including roads, are everywhere set back, raised, or protected in various ways from the ocean, using grade change, landforms, wetland habitats, open space, pervious areas, and various types of green infrastructure as sponges or buffers to create resiliency and address the increased vulnerability of our communities. Landscape architects in the US and other progressive countries represent the future in this immense effort, leading multidisciplinary teams and appropriating large federal funds to meet these challenges through research, modeling, and testing new technologies. Charlotte Amalie deserves the same.